thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

The Temple of Apollo at Stourhead: Architecture and Astronomy

2021

2021

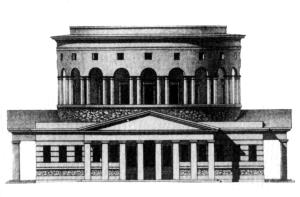

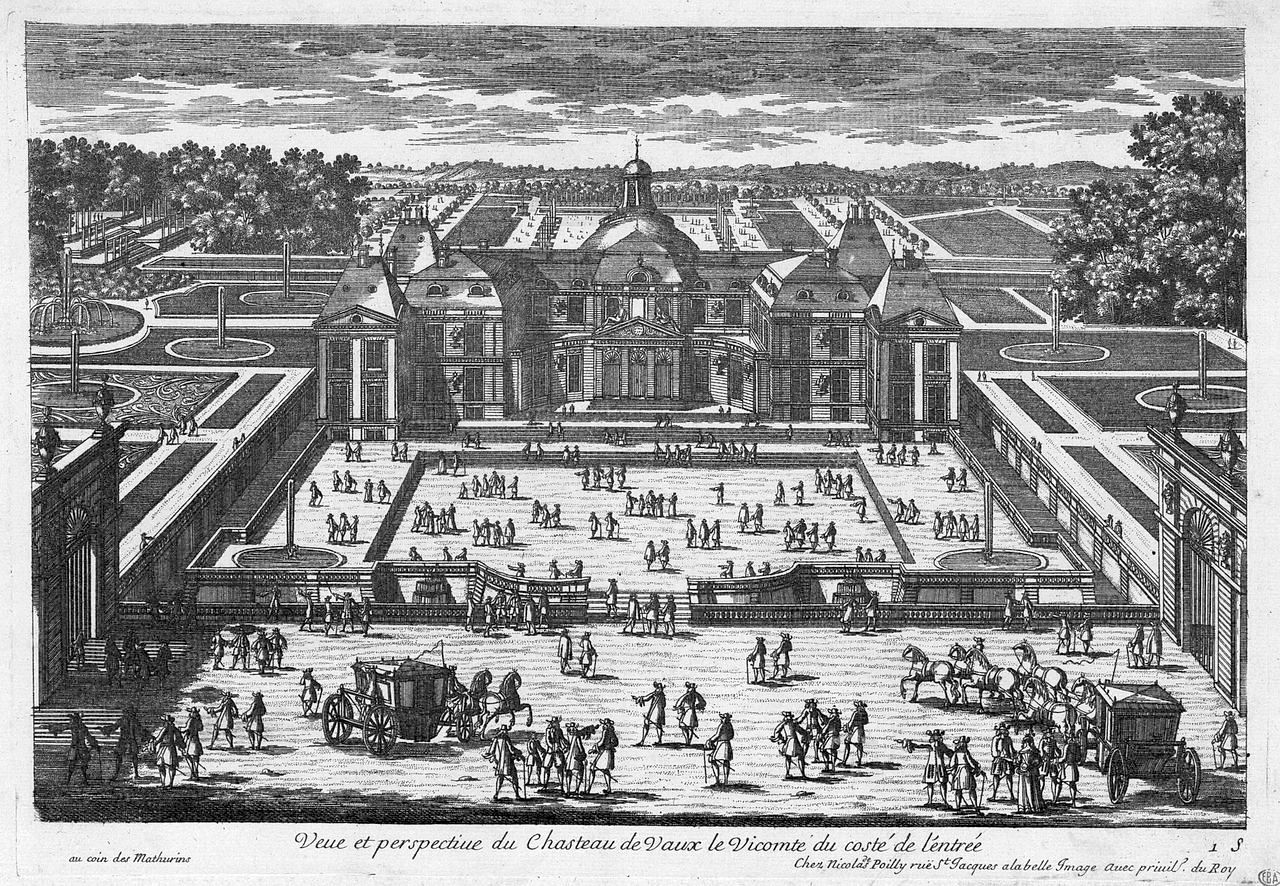

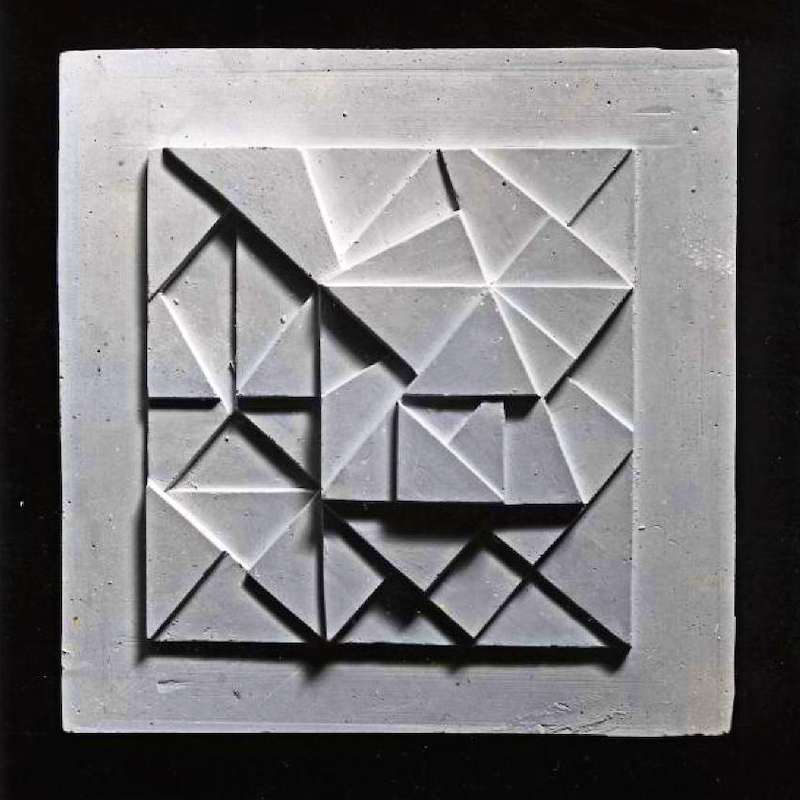

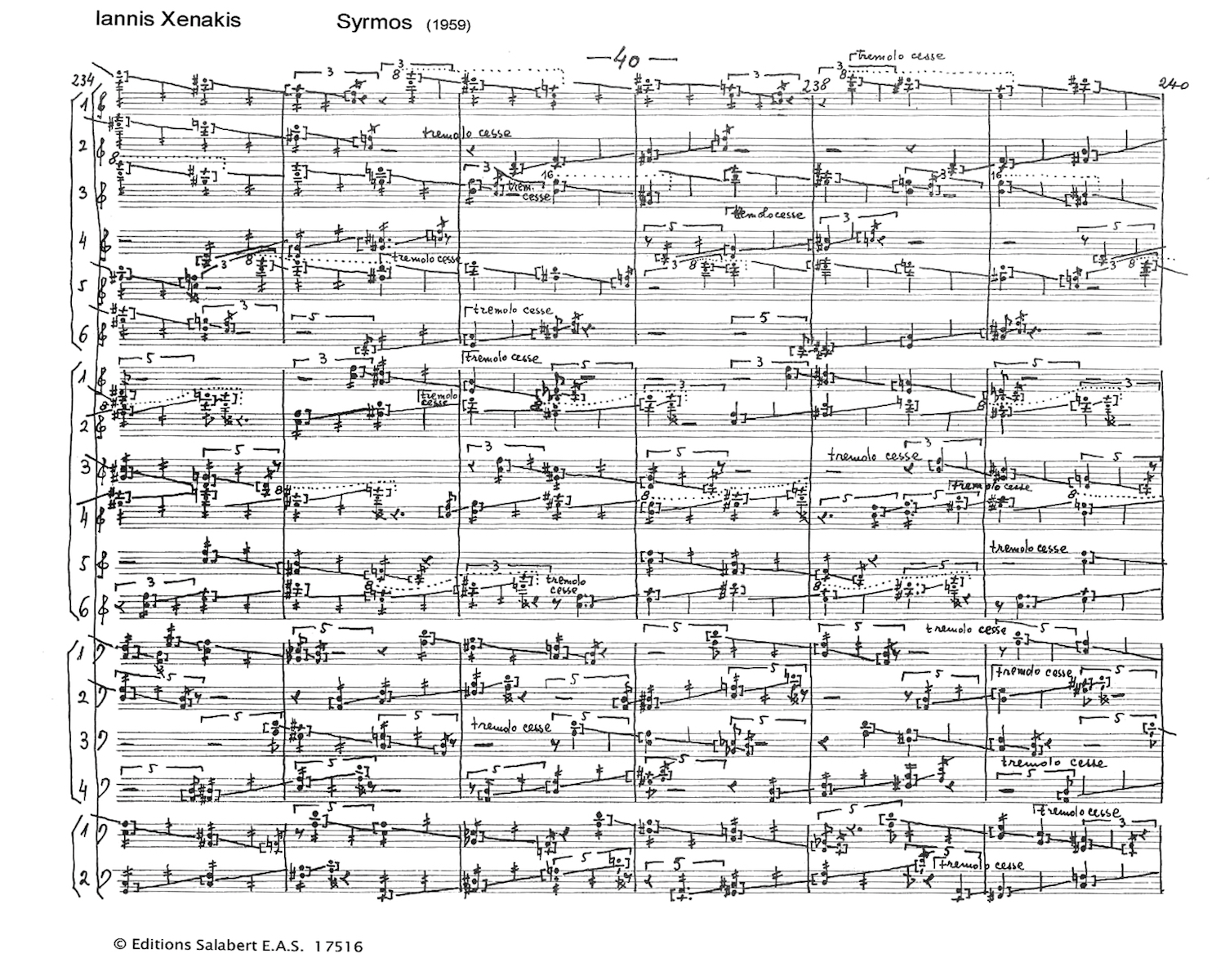

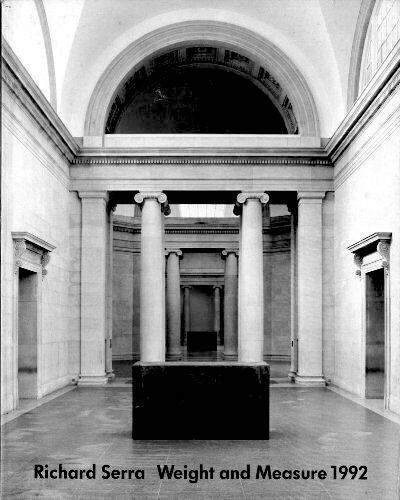

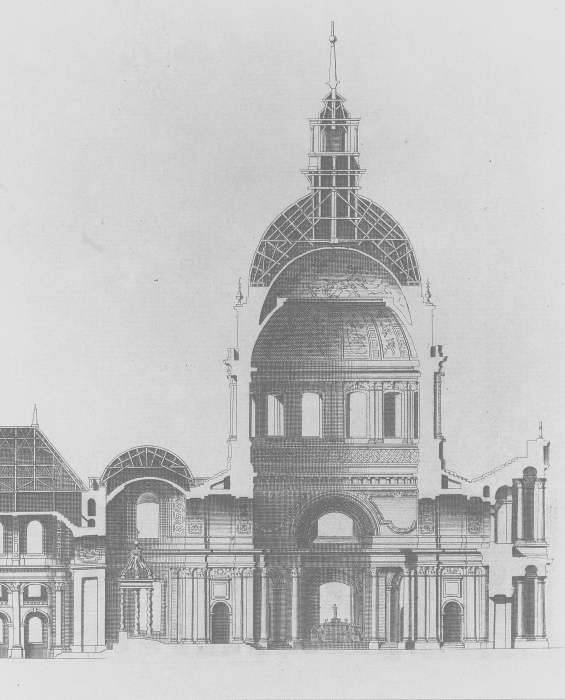

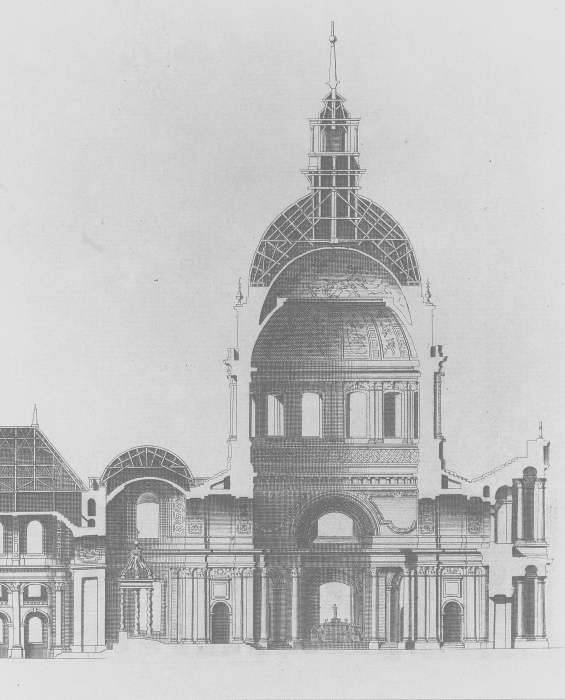

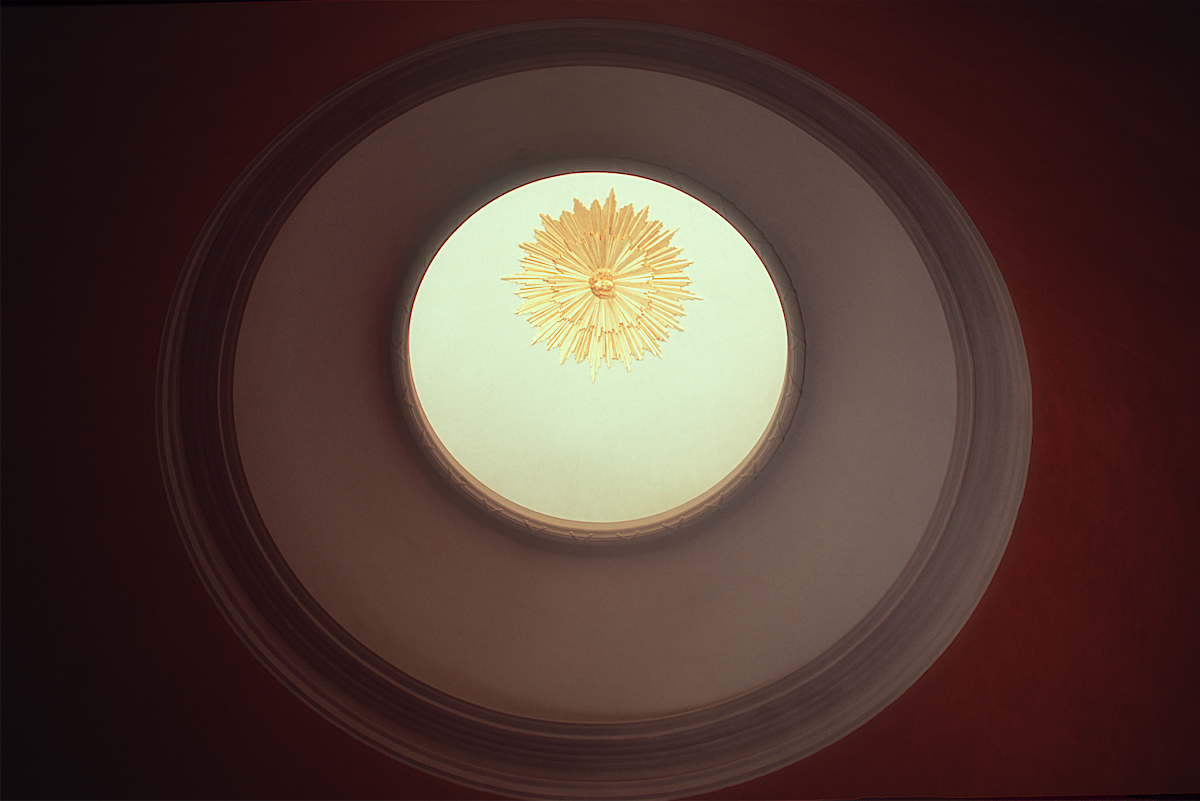

Jules Hardouin-Mansart: Royal Chapel, Les Invalides, Paris (1676)

section showing the double internal domes

section showing the double internal domes

roll over for illustration of optical path

The Temple of Apollo at Stourhead: Architecture and Astronomy

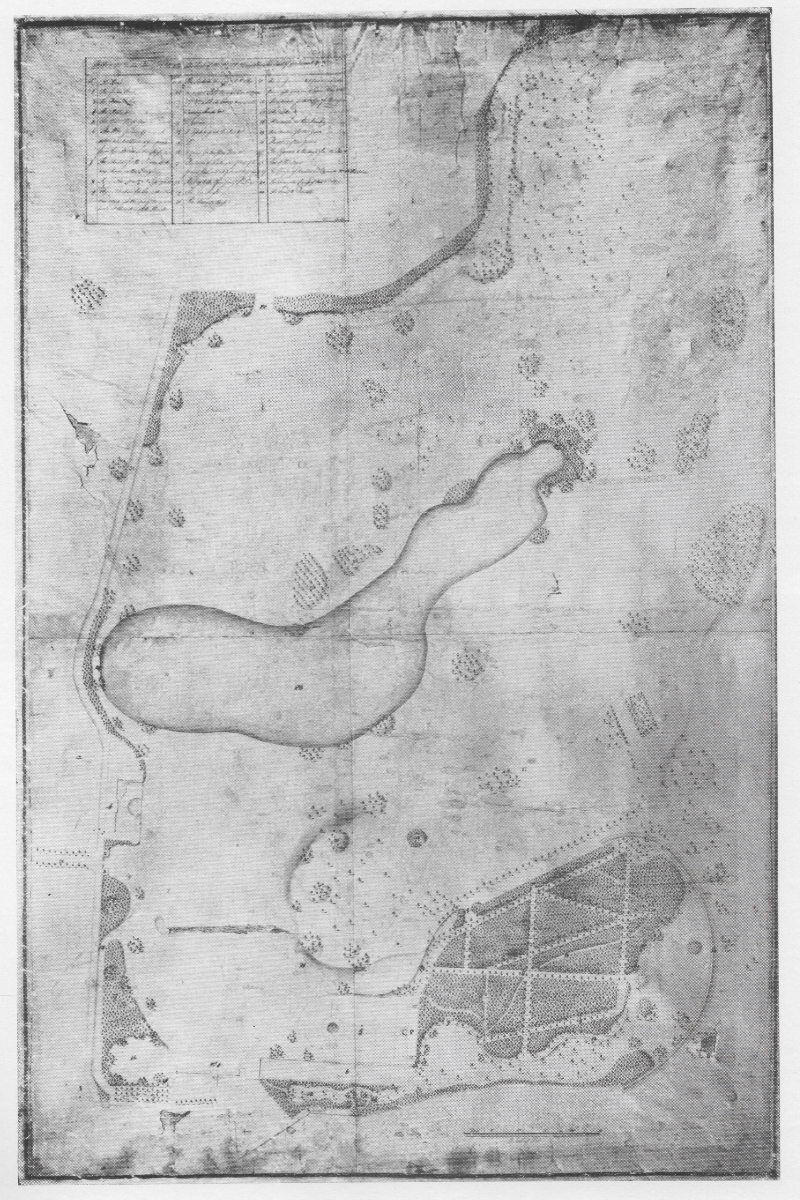

The visitor to the Temple of Apollo at Stourhead might be surprised that it had any connection to French Baroque architecture, let alone the developing science of optical astronomy, not least because Stourhead is regarded as one of the first, and possibly the greatest, English landscape garden. In the early 18th century, architects such as William Kent (1685?–1748) at Stowe and Henry Flitcroft (1697-1769) at Stourhead recreated the Arcadian idyll depicted in the paintings of Claude (1604/5?-1682), not only as celebrations of topography but as the embodiment of intellectual and political ideals. Claude, although French, lived and practiced in Rome, and used the Roman campagna as the basis of his paintings. As the 18th century progressed the narrative aspect faded in significance in favour of the - native - topographical, exemplified by the work of the landscape architect Capability Brown (1716-83).

Henry Flitcroft: Temple of Apollo, Stourhead, seen across the lake

© Thomas Deckker 2013

© Thomas Deckker 2013

The house at Stourhead (1721-25), for Henry Hoare, was by Colen Campbell (1676-1729), one of the pioneers of the Palladian style in Britain. Campbell’s house closely followed Palladio’s own villas, such as the Villa Foscari (1558-60) in the Veneto, and, as at the Villa Foscari, the site was originally not extensively landscaped. The creation of an Arcadian idyll was evidently in Hoare’s mind, however; he apparently owned Claude’s Landscape with Aeneas at Delos (1672), now in the National Gallery, London, and a copy by John Plimmer, Procession to the Temple of Apollo at Delos (1759-60), remains in the house. Claude’s Landscape could have provided the template for the combination of temples and landscape seen today.

Claude: Landscape with Aeneas at Delos (1672)

© National Gallery, London NG1018

© National Gallery, London NG1018

Flitcroft's Temple of Apollo (1757) is one of the main buildings of Hoare's Arcadian landscape and, despite the antipathy of the Whig Palladians to the Royalist baroque, resembles a French baroque dome. Apollo, as the Greek and Roman God of the Sun, was crucial to French baroque architecture: Louis XIV saw himself as the ‘Sun King’, embodied in the Fountain of Apollo at the Palace of Versailles. The connection between the Temple of Apollo and French baroque architecture was not built on this foundation, however, but on what might be called the architectural consequences of optical astronomy.

Henry Flitcroft: Temple of Apollo, Stourhead, from the garden

© Thomas Deckker 2013

© Thomas Deckker 2013

Henry Flitcroft: Temple of Apollo, Stourhead, view through the oculus of the inner dome to the roundel of the sun

© Thomas Deckker 2013

© Thomas Deckker 2013

The great historian of the baroque, George L. Hersey, pointed out in Architecture and Geometry in the Age of the Baroque (University of Chicago Press, 2001) that Jules Hardouin-Mansart used a double internal dome at Louis XIV's Chapel at Les Invalides (1676), to give the impression of looking through an oculus onto a more distant scene of the heavens, in direct simulation of a telescope. The antique oculus was plainly visible in the Pantheon, Rome, and widely copied usually with glazing, but the double dome was an invention of northern Europe, for obvious reasons. And so it is at the Temple of Apollo at Stourhead: the viewer looks through the oculus of the inner dome onto a representation of the sun on the ceiling of the upper dome. The lunette windows on the drum light, not the central hall, but the space between the domes, making the sculpture of the sun unexpectedly bright. Flitcroft was not as orignal or intellectual an architect as the French baroque masters and it is doubtful if he had any interest in astronomy. It is more likely that, as a practicing architect, he knew and admired the Mansarts’ work (as did Christopher Wren), and formal connections are evident between the Temple of Apollo and François Mansart’s dome of Val-de-Grâce, in particular the regular girdle of columns surrounding the drum, or Jules Hardouin-Mansart’s double internal dome.

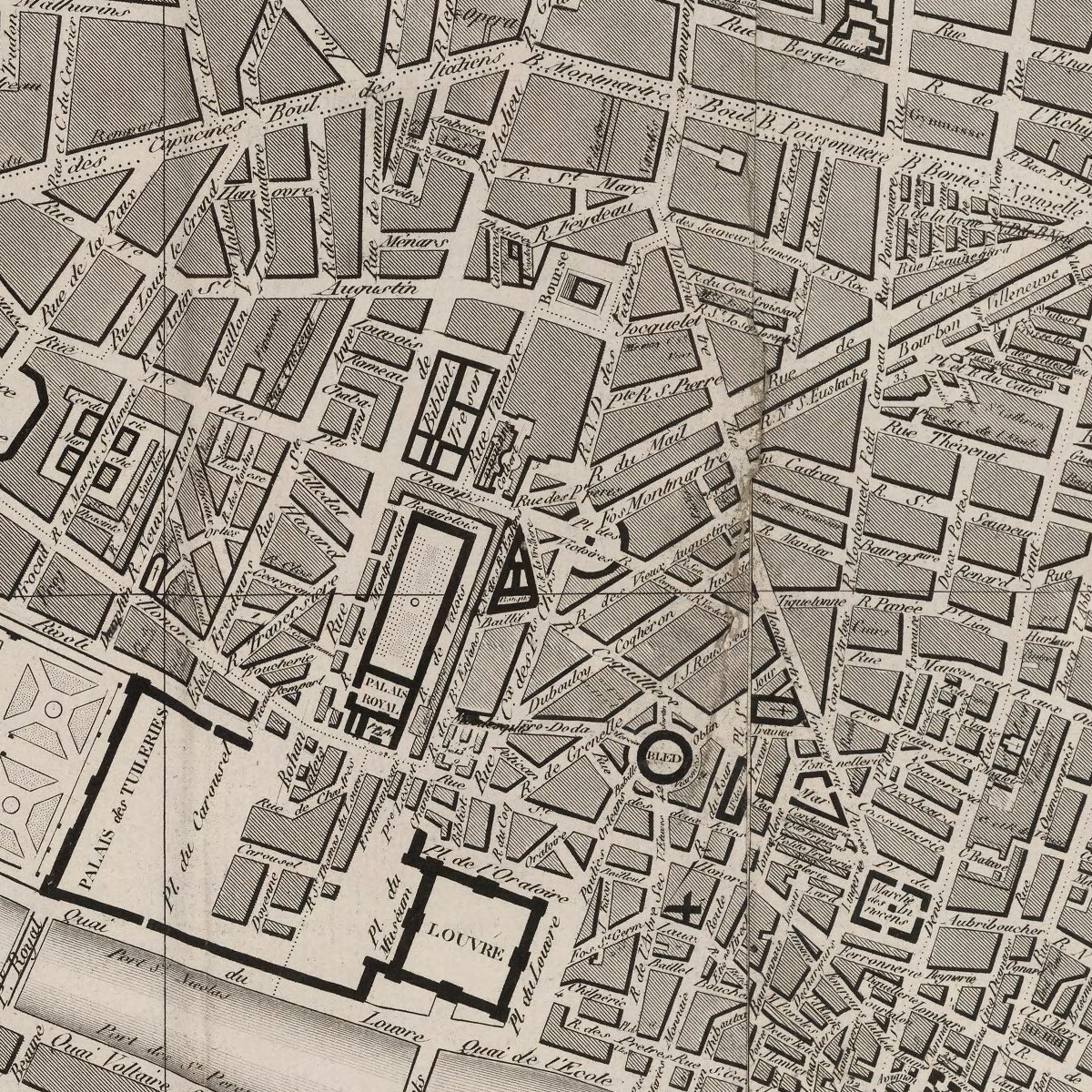

Hersey noted the close relationship between architects and astronomy at both practical and theoretical levels. Mathematics underlay music, astronomy and architecture in the period. Claude Perrault (1613-88), architect of the East Wing of the Louvre (1667-70), was a physician and musical theorist as well as a founder, in 1666, of the Académie Royale des Sciences. Christopher Wren (1632-1723), architect of St Paul’s Cathedral (1670-1698), had been Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford University and a founder of The Royal Society in 1660, before being appointed Surveyor of the King’s Works in 1669; this is described in some detail in Anthony Gerbino's and Stephen Johnston's Compass and Rule: Architecture as Mathematical Practice in England 1500-1750 (Yale University Press 2009).

Hersey noted the close relationship between architects and astronomy at both practical and theoretical levels. Mathematics underlay music, astronomy and architecture in the period. Claude Perrault (1613-88), architect of the East Wing of the Louvre (1667-70), was a physician and musical theorist as well as a founder, in 1666, of the Académie Royale des Sciences. Christopher Wren (1632-1723), architect of St Paul’s Cathedral (1670-1698), had been Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford University and a founder of The Royal Society in 1660, before being appointed Surveyor of the King’s Works in 1669; this is described in some detail in Anthony Gerbino's and Stephen Johnston's Compass and Rule: Architecture as Mathematical Practice in England 1500-1750 (Yale University Press 2009).

Sectioned (longitudinally) terrestrial refracting telescope

Science Museum Group Collection 1917-49

Science Museum Group Collection 1917-49

Note the inner barrel within the main barrel, interpreted by Jules Hardouin-Mansart at Les Invalides as a double internal dome.

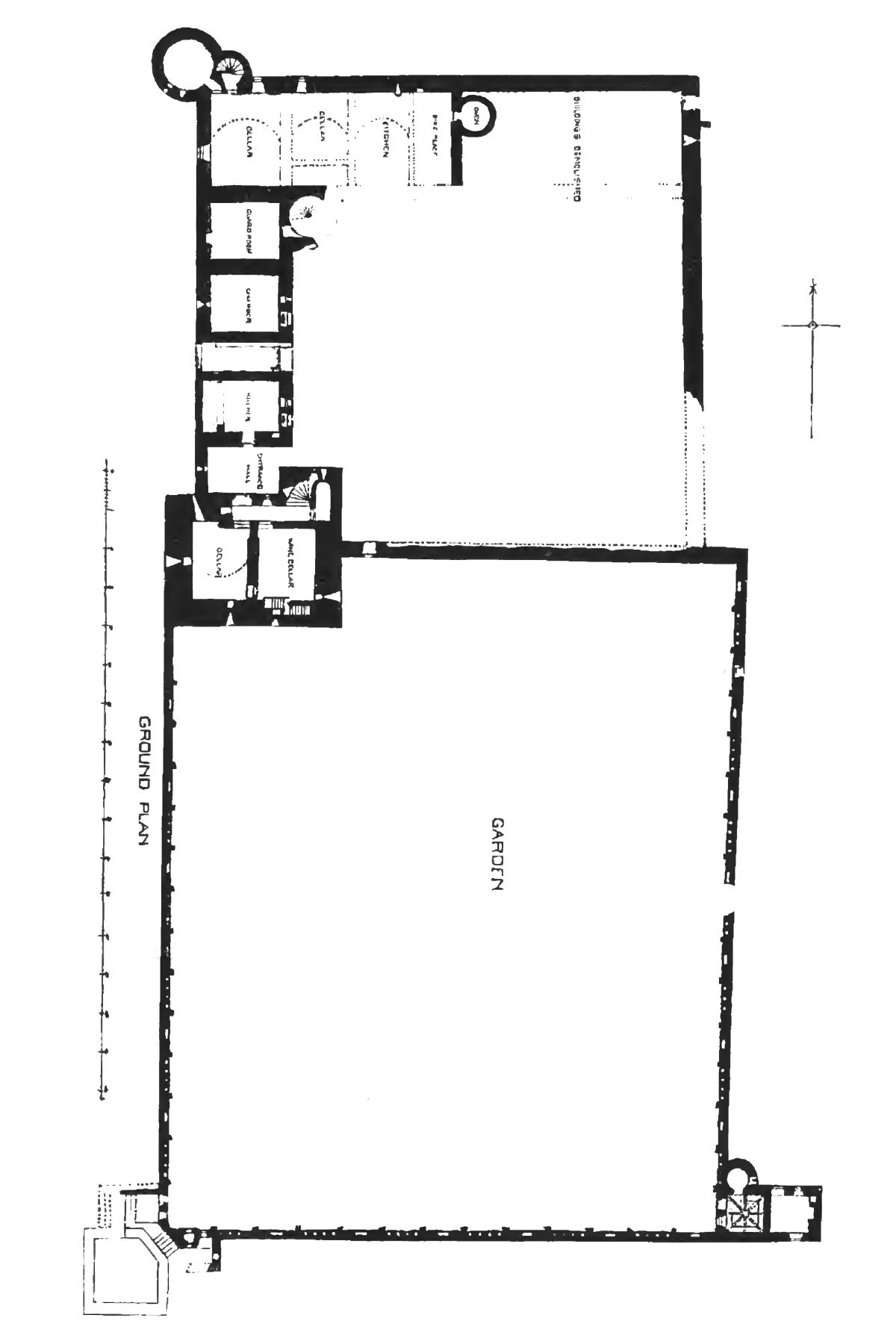

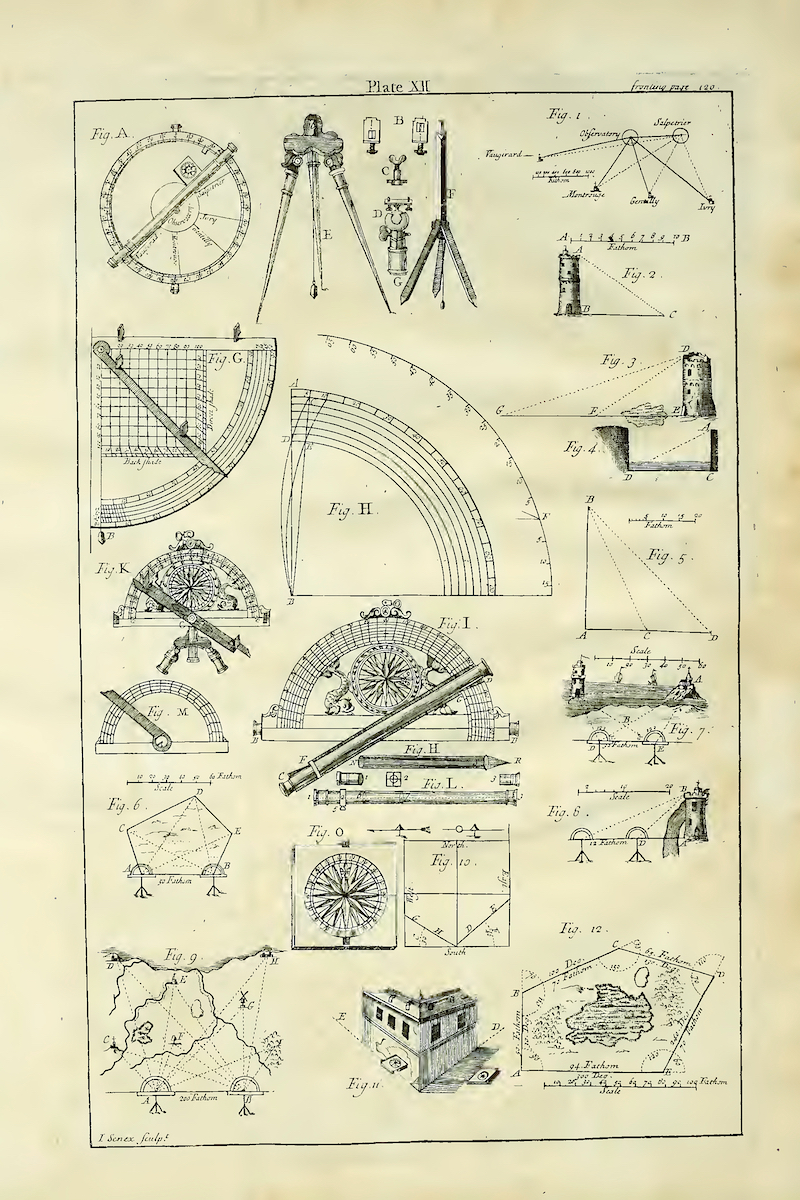

On a practical level, the instruments used (to measure or set out) in mathematics, astronomy and architecture were inventions of the period. Optical instruments had terrestrial as well as celestial uses. The newly-discovered theodolite and level, essential to setting out large buildings and landscapes, were made more accurate by the use of the telescope for sighting long distances and the microscope for reading vernier scales. The astronomer Jean Picard of the Académie Royale des Sciences, famous at the time for accurately measuring the diameter of the Earth, made a telescopic level for setting out the gardens at Versailles. The large and complex English landscape gardens, especially the large bodies of water, would have been unthinkable without the advances in optics. Edmund Stone's builders treatise The Construction and Principal Uses of Mathematical Instruments, including telescopic levels and amusingly how to survey towers across bodies of water, was published in London in 1728.

Plate XII from Edmund Stone: The Construction and Principal Uses of Mathematical Instruments (London 1728)

It is no wonder that architects of the importance and calibre of Jules Hardouin-Mansart sought to represent the new discoveries in mathematics in architecture. How satisfying for Flitcroft to repurpose this for the most English of gardens.

Update December 2023

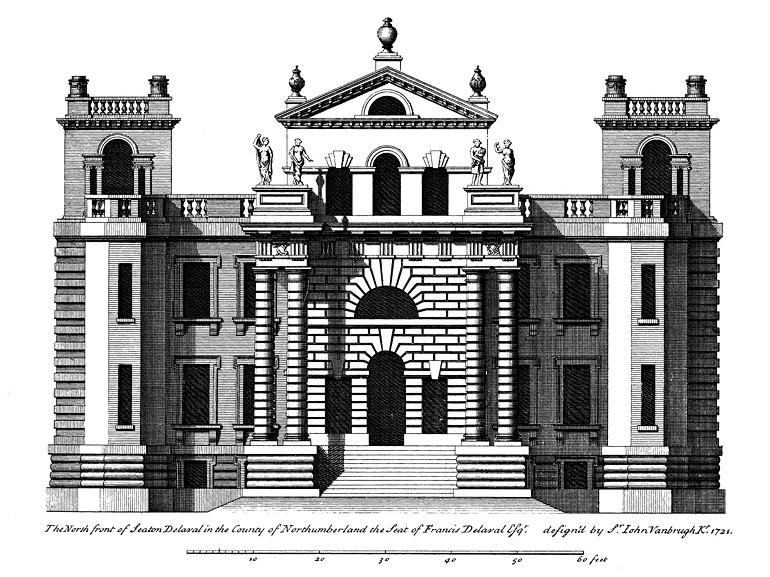

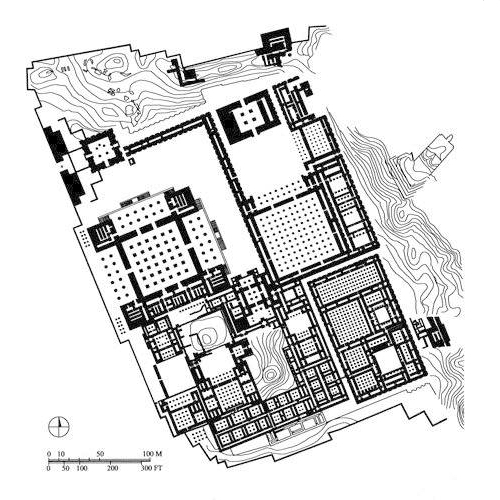

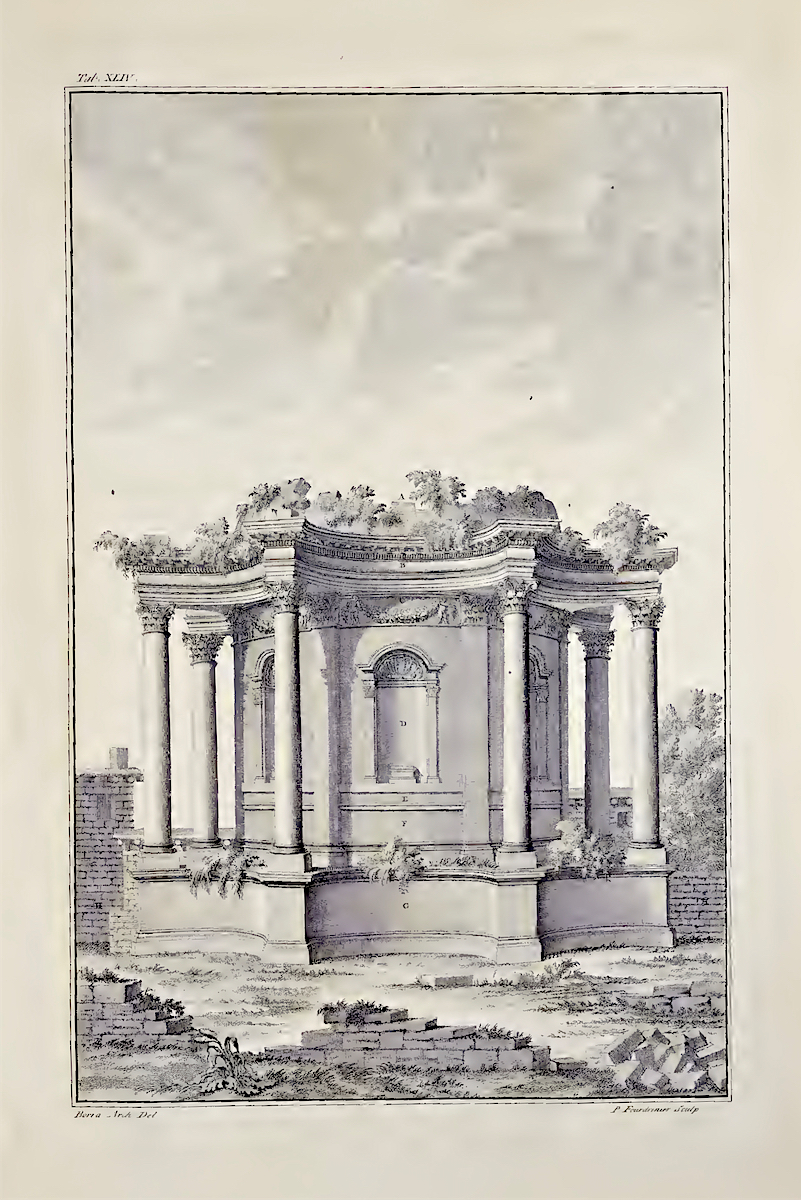

Plate XLIV from Robert Wood: The Ruins Of Balbec [London 1757]

The Circular Temple (now known as the Temple of Venus), Baalbek

The Circular Temple (now known as the Temple of Venus), Baalbek

Gill Hedley has pointed out, in her encyclopaedic history of Henry Flitcroft, that the drum of the Temple of Apollo at Stourhead was based on the Circular Temple (now known as the Temple of Venus, from the second or early third century AD) at Baalbek, which had been illustrated by Robert Wood in 1757. It is entirely possible to imagine Flitcroft giving a novel twist to a conventional baroque structure, to accentuate its Arcadian appeal, and the building looks more archaic than, for example, William Kent's Temple of Ancient Virtue at Stowe of the 1730s. The Arcadian appeal certainly did not come from anything to be seen at Baalbek; Wood described the ruins as situated in a very decayed and perilous Ottoman village.[1]

William Kent: Temple of Ancient Virtue, Stowe, seen across the lake

© Thomas Deckker 2015

© Thomas Deckker 2015

Footnotes

1. Gill Hedley: The Ingenious Mr Flitcroft: Henry Flitcroft, Palladian Architect [Lund Humphries 2023]. This book was commissioned by Hoare's Bank, descendants of the original creator of Stourhead.

Robert Wood: The Ruins Of Balbec, otherwise Heliopolis in Cœlosyria [London 1757]. Heliopolis, City of the Sun, was the Roman name (in Greek) for the city, named after Heliopolis in Egypt. ↩

Robert Wood: The Ruins Of Balbec, otherwise Heliopolis in Cœlosyria [London 1757]. Heliopolis, City of the Sun, was the Roman name (in Greek) for the city, named after Heliopolis in Egypt. ↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2021

London 2021