thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

Seaton Delaval: the aesthetic castle

2021

2021

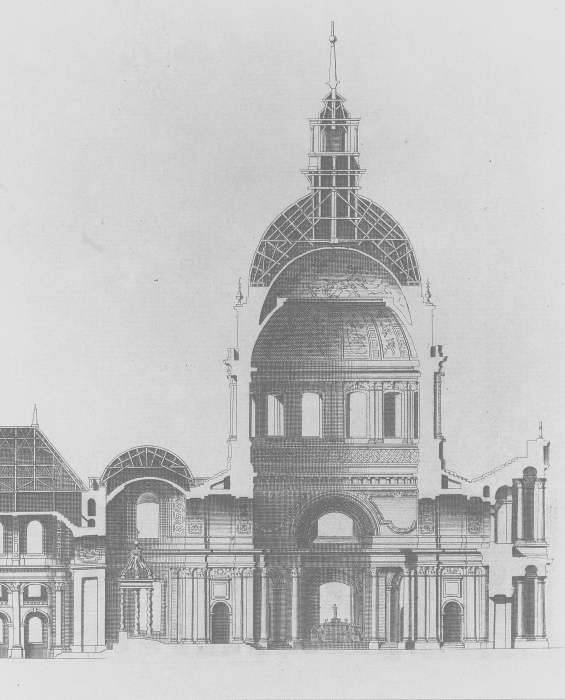

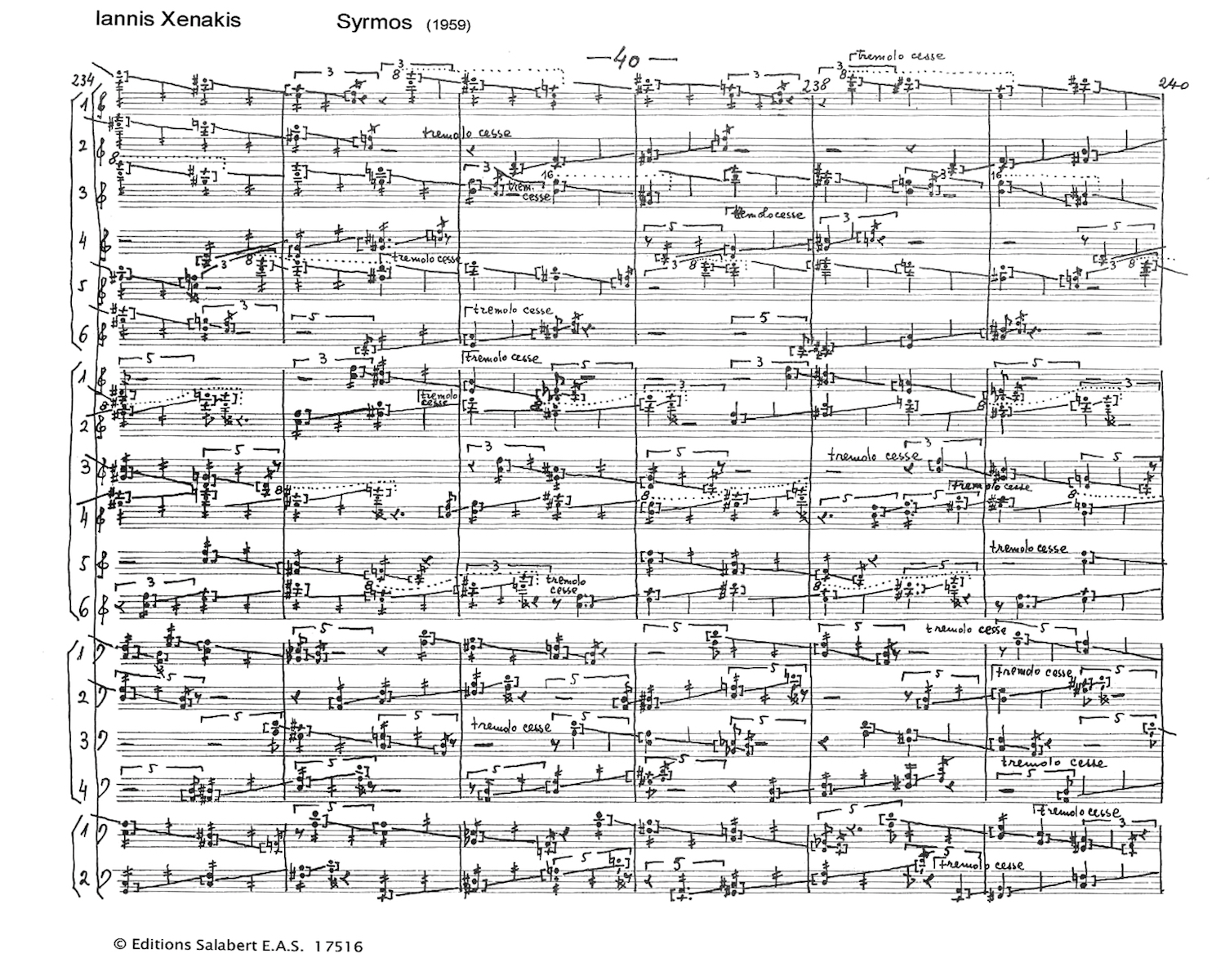

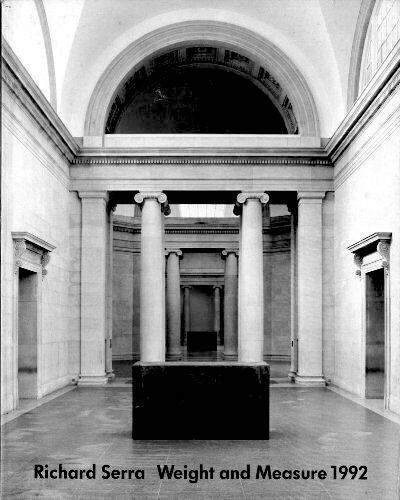

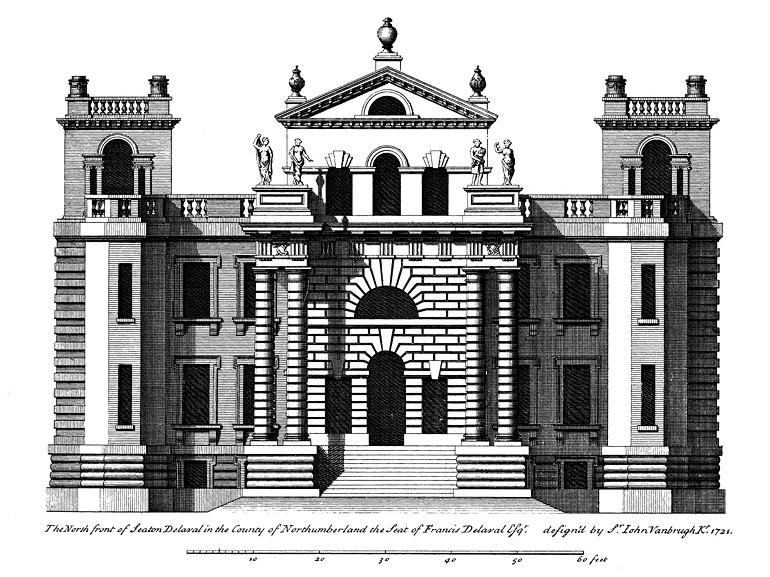

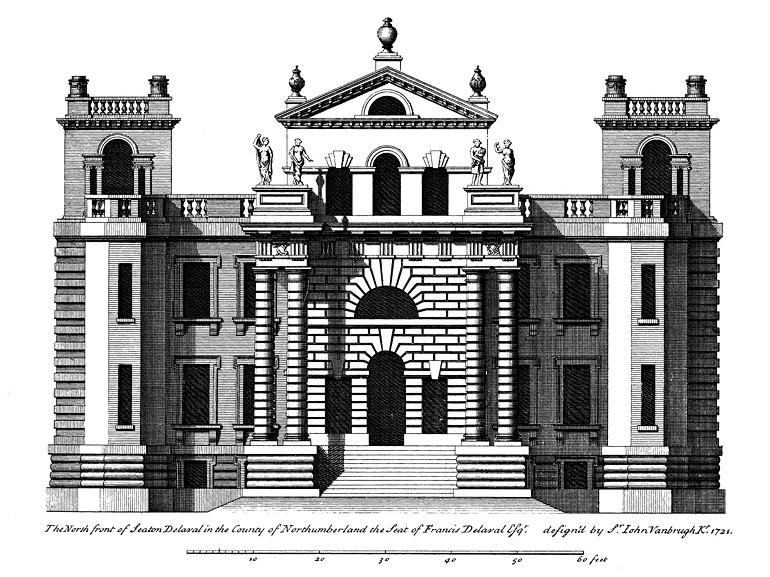

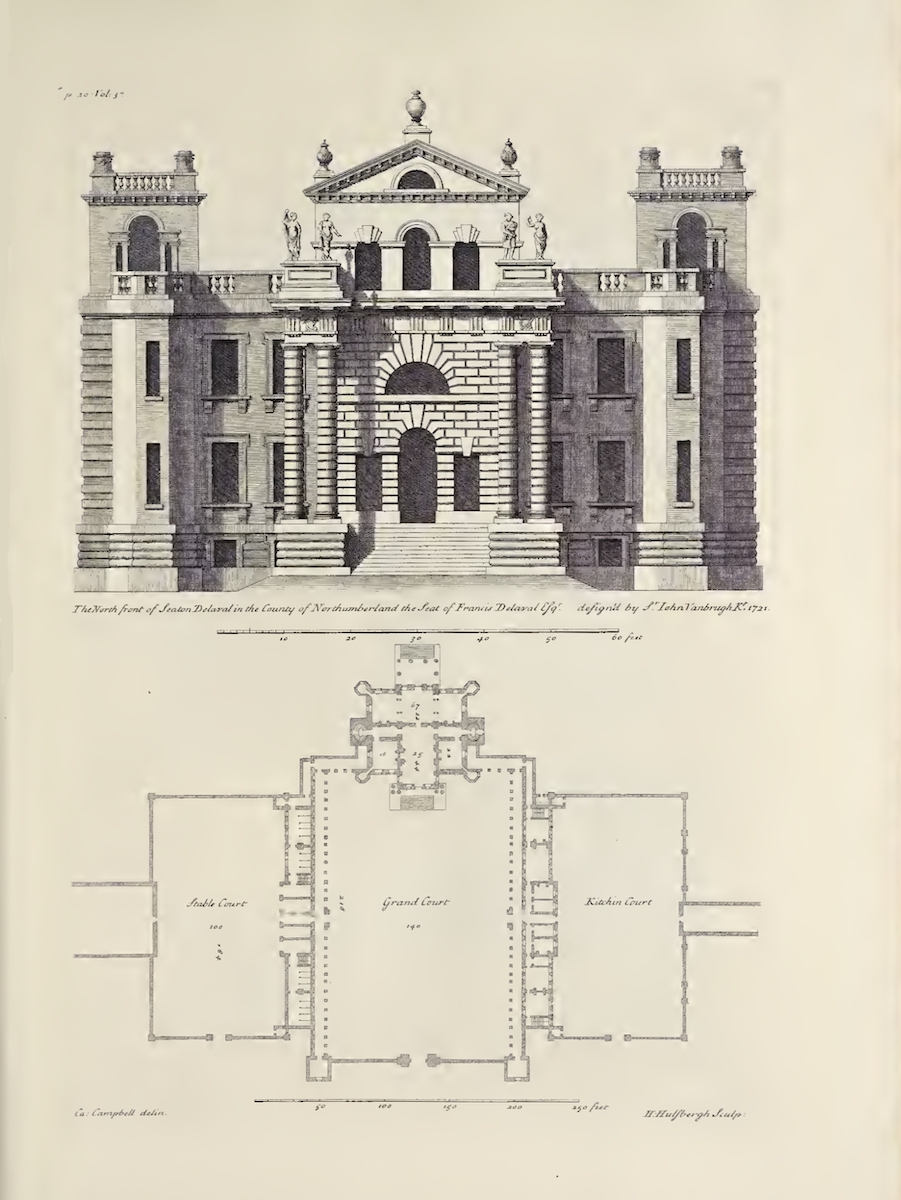

Sir John Vanbrugh: Seaton Delaval, Northumberland (1720-28)

from Colen Campbell: Vitruvius Britannicus vol 3 (1725)

from Colen Campbell: Vitruvius Britannicus vol 3 (1725)

Seaton Delaval: the aesthetic castle

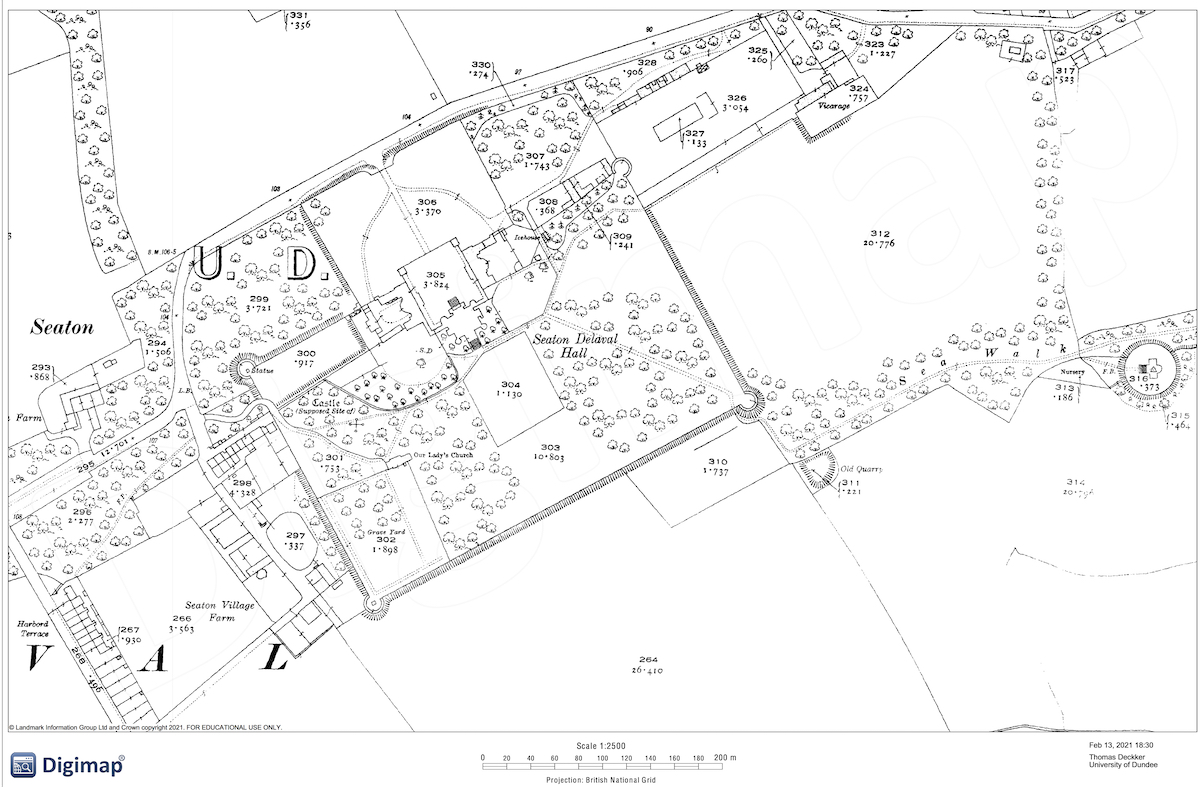

Sometimes its the small things in buildings that reveal the architects's private thoughts, with what ideas they were playing in the design of a building. At Seaton Delaval that small thing is the circular bastions on the corners of a wall that defines the inner garden. What are the wall and bastions for? The wall does not protect the entrance front, as the entrance court breaks it, and it does not define the limits of the landscape on the garden side. The circular bastions are symbolic, like the house itself, of castle architecture in general - one unusual example and possible reference, Warkworth, lies just up the coast - and of another earlier and equally celebrated symbolic castle in particular - Chambord.

Sir John Vanbrugh: Seaton Delaval, Northumberland (1720-28)

© Thomas Deckker 2017

© Thomas Deckker 2017

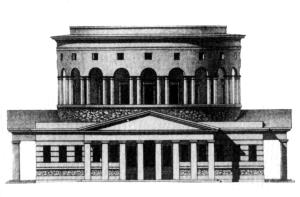

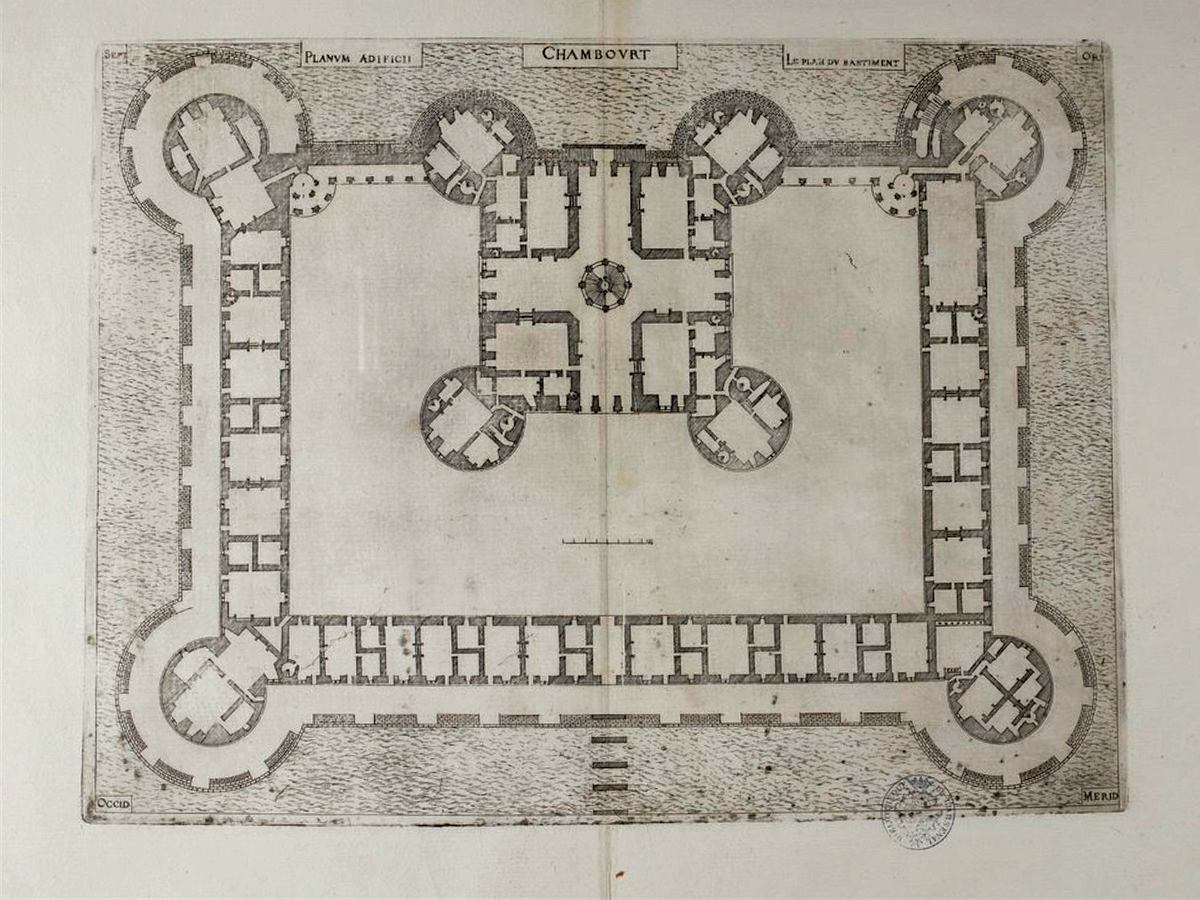

Seaton Delaval, Northumberland (1720-28) by Sir John Vanbrugh is considered, quite rightly, as defining an English approach to baroque architecture, of a proud and idiosyncratic piling up all kinds of architectural references, as opposed to rational, austere and professional French architects like François Mansart and Louis Le Vau. Underlying it all is a sense that it was, or used to be, or perhaps still could be, a castle, with its octagonal corner towers and heavy rustication that extend what should be the base up the full height of the wall. The word castle must be qualified, however: it cannot possibly refer to the fortified military encampments of the middle ages, with solid walls and brutal enceintes and donjons, but to its highly symbolic reinterpretation in the luxurious chateaux that began with Chambord, Blois and Amboise in the Loire in the 16th century.

Sir John Vanbrugh: Seaton Delaval

from Colen Campbell: Vitruvius Britannicus Vol 3 (1725)

from Colen Campbell: Vitruvius Britannicus Vol 3 (1725)

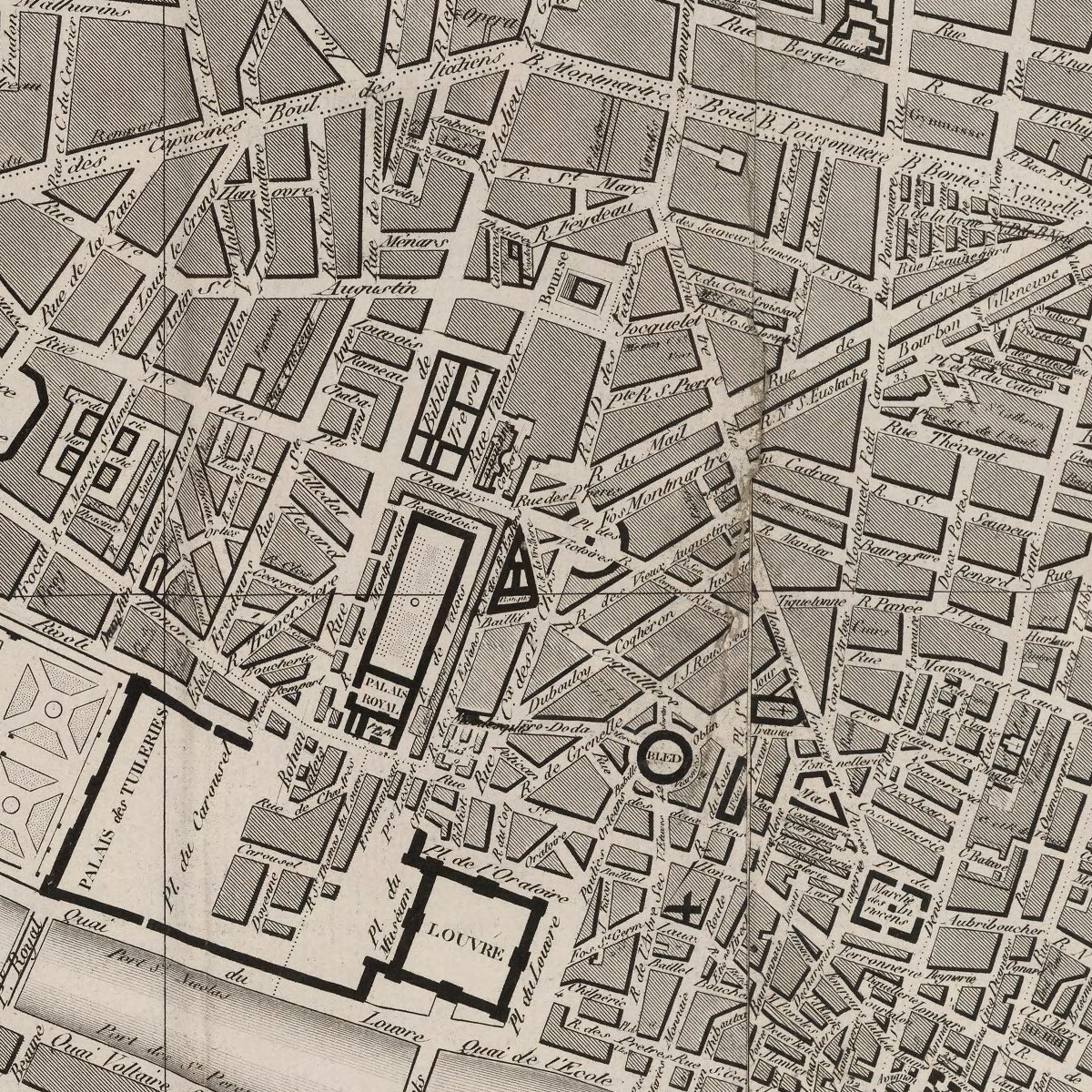

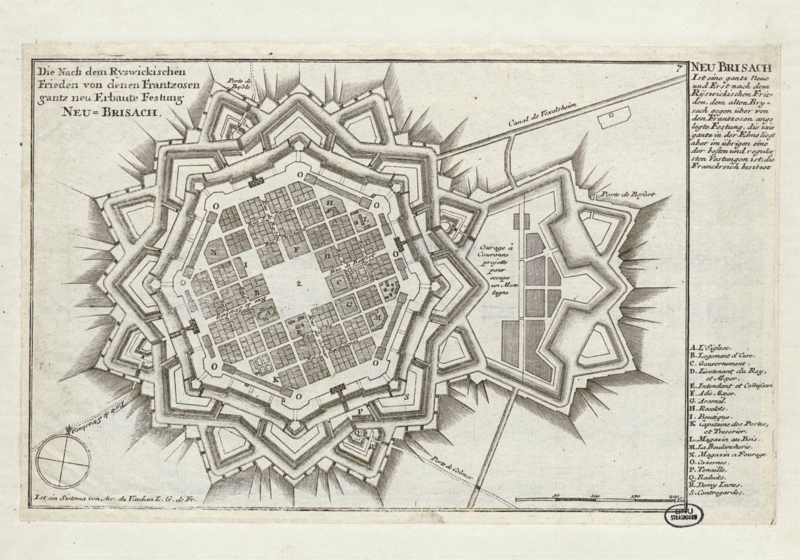

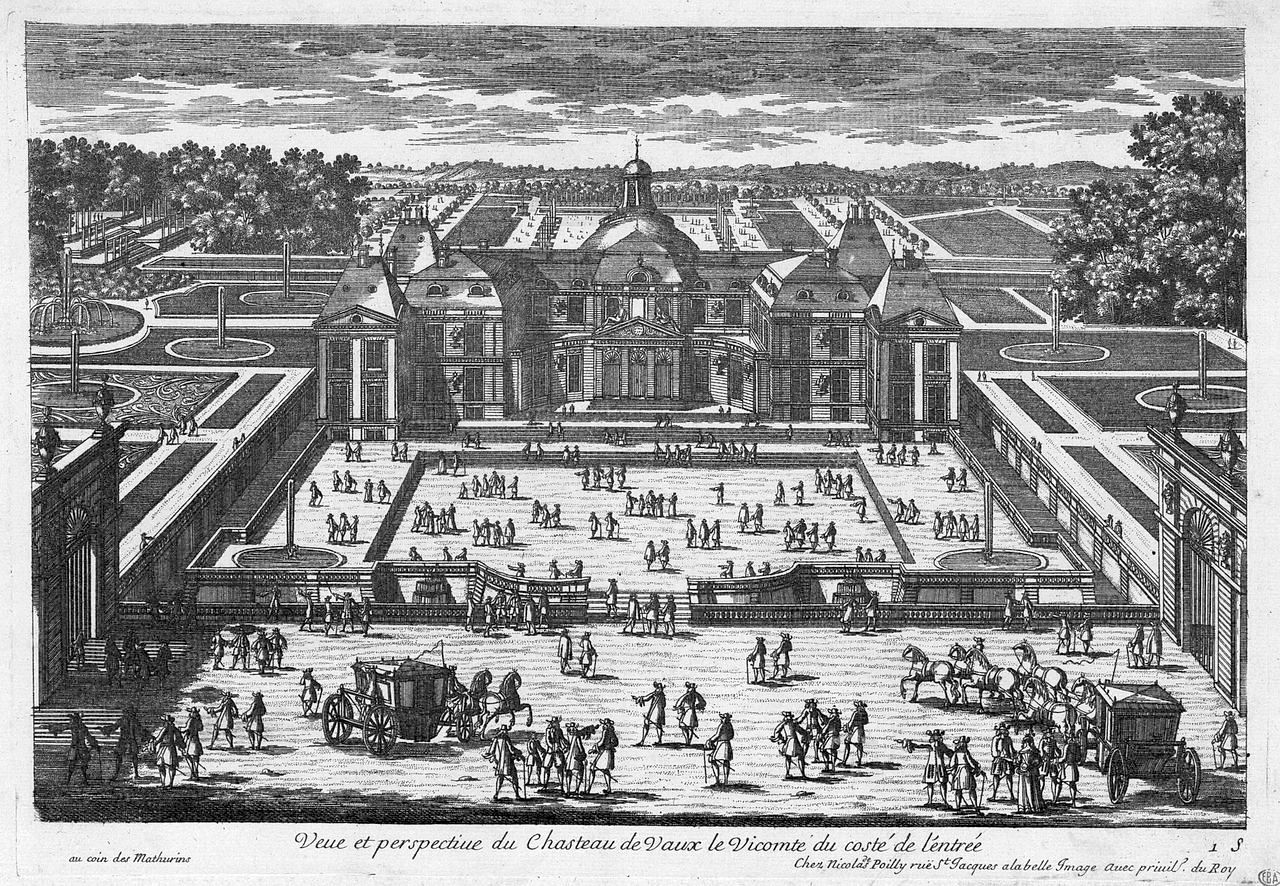

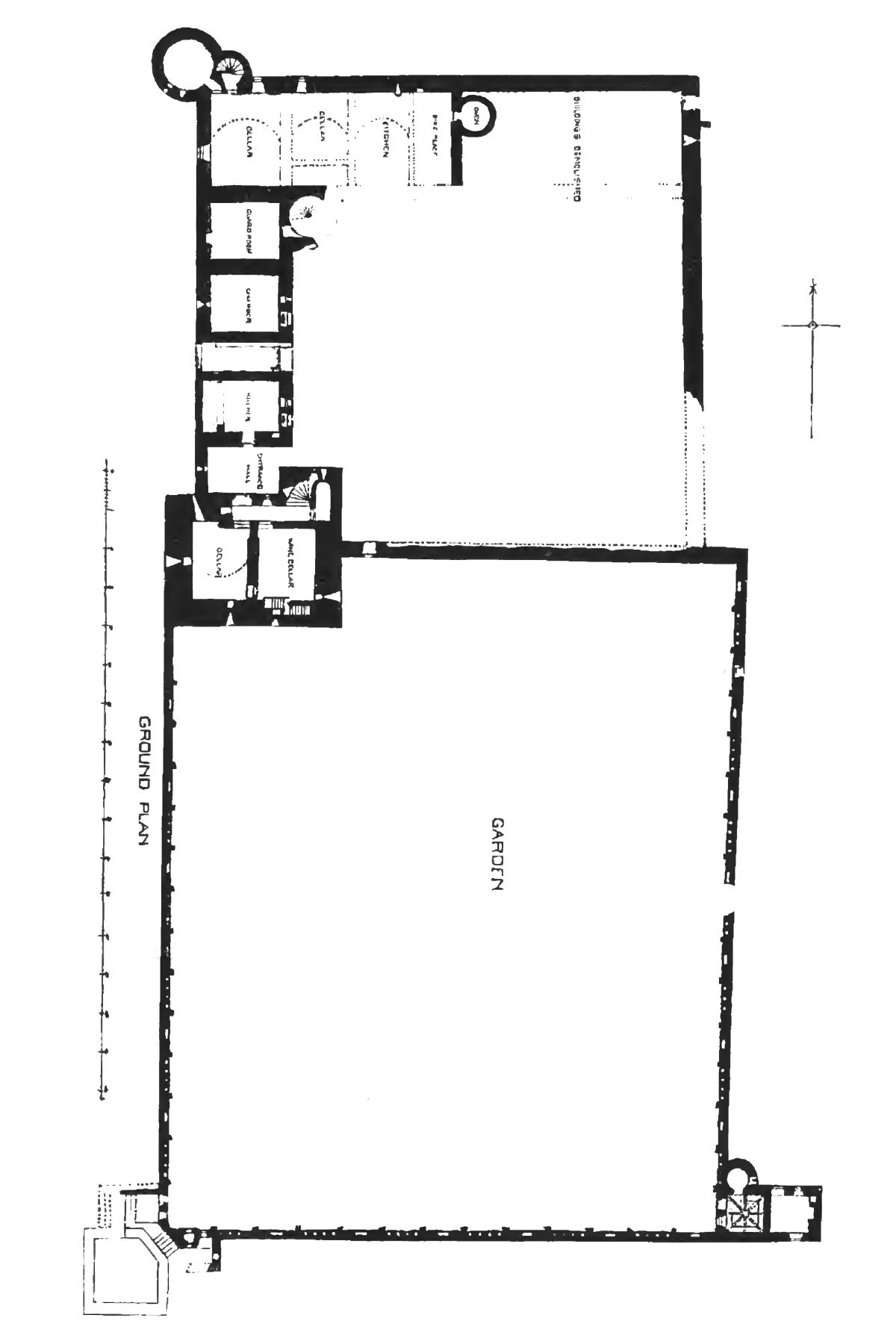

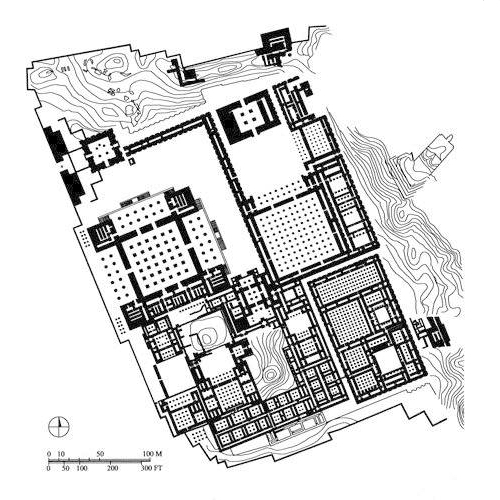

In many ways the arrangement of forms and spaces at Seaton Delaval is literally that of a French chateau of the baroque period. Compare the plan to that of Le Vau's Vaux-le-Vicomte (1657-61). The main elements of the plan at Vaux-le-Vicomte are a transverse corps de logis across an axial sequence from a rectangular entrance court, through formal water basins, to a colossal forest landscape extending several miles towards the horizon, punctuated by a statue of Hercules 1000 metres distant. The sequence is the same at Seaton Delaval: a landscaped avant-cour, a cour defined by robust low buildings, an axial sequence though the house ending with a transverse salon, a formal garden and an extensive landscape, with a pond 500 metres and obelisk 1000 metres distant. This connection is unambiguous.

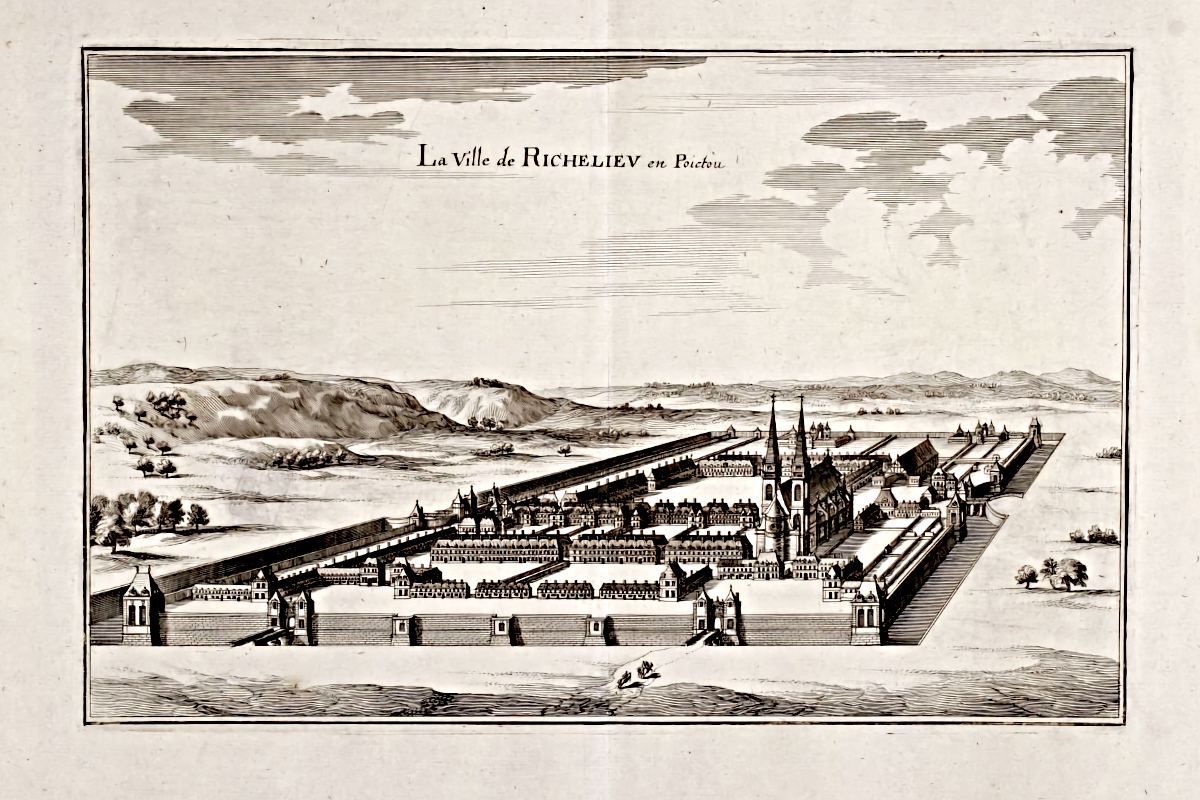

Chateau de Chambord

from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents bastiments de France (1579)

from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents bastiments de France (1579)

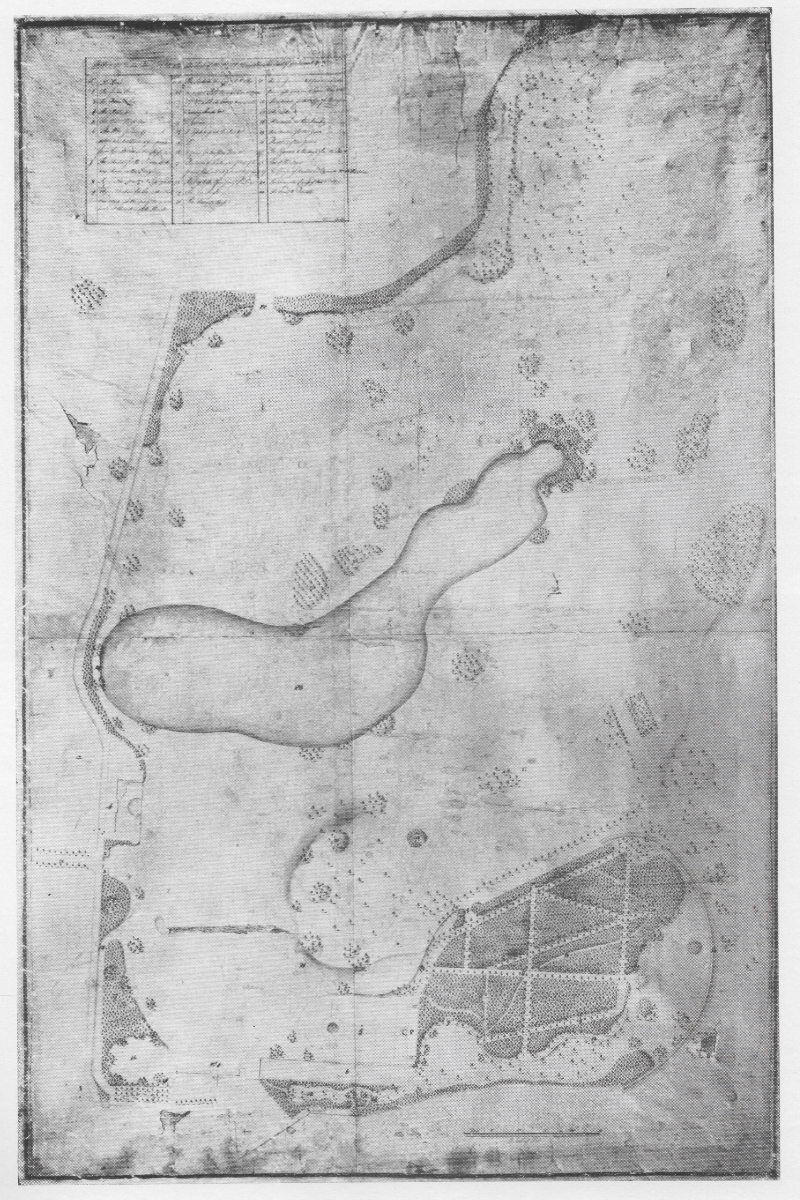

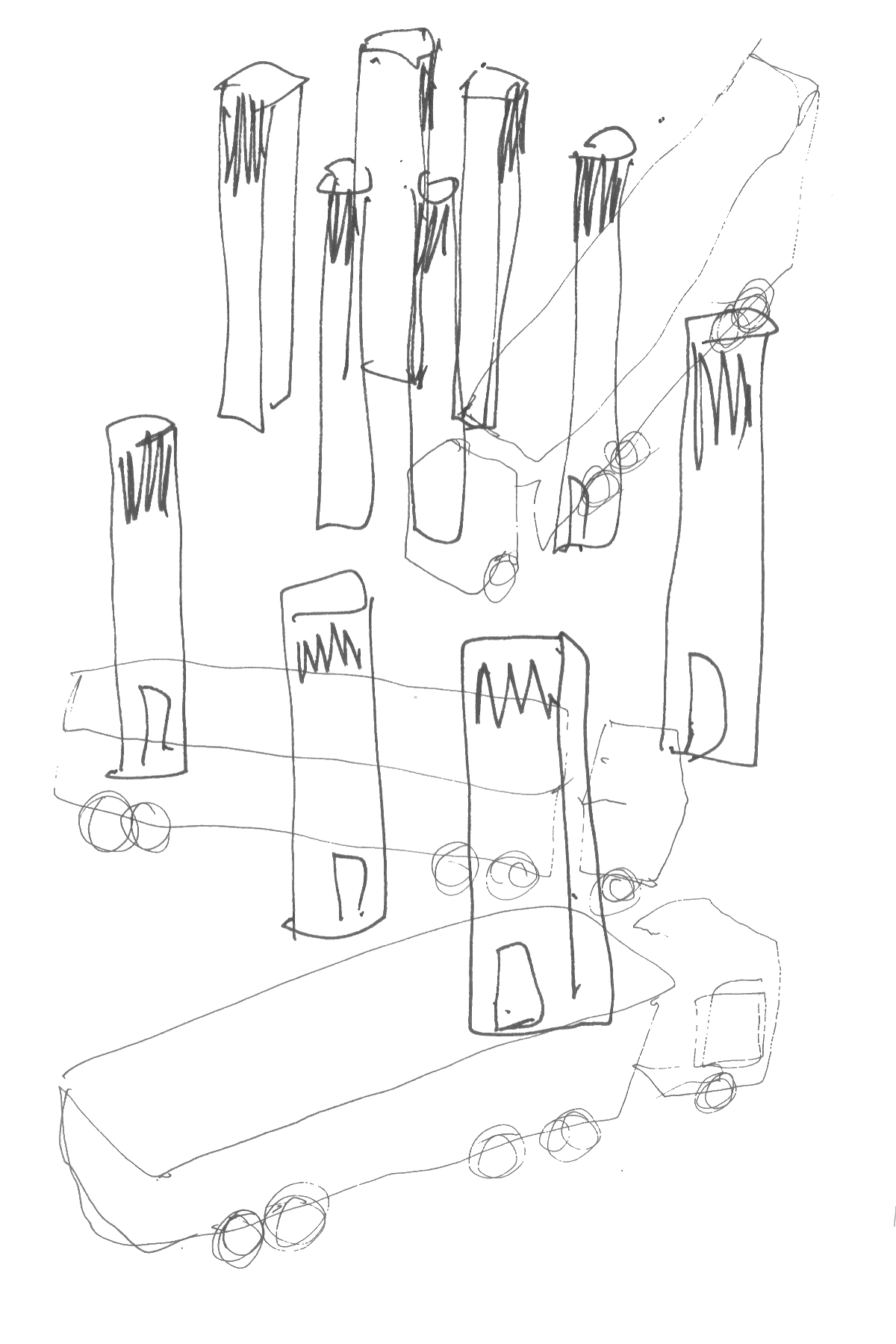

In other ways, however the plan recalls that of Chambord (1519-), attributed to the Italian architect Domenico da Cortona who, with Sebastiano Serlio and Leonardo da Vinci, brought renaissance architecture to France. Chambord was built as a hunting lodge for François I, so had no gardens outside the walls, but was set in a forest criss-crossed by allées for hunting. It was quite symbolically a castle: a romanticised vision of French medieval life evident in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Note in particular the square inner 'donjon' with corner towers, and the rectangular outer 'enceinte' and moat wall with corner bastions. The form of the moat wall is in exactly the same form and position as the garden wall at Seaton Delaval.

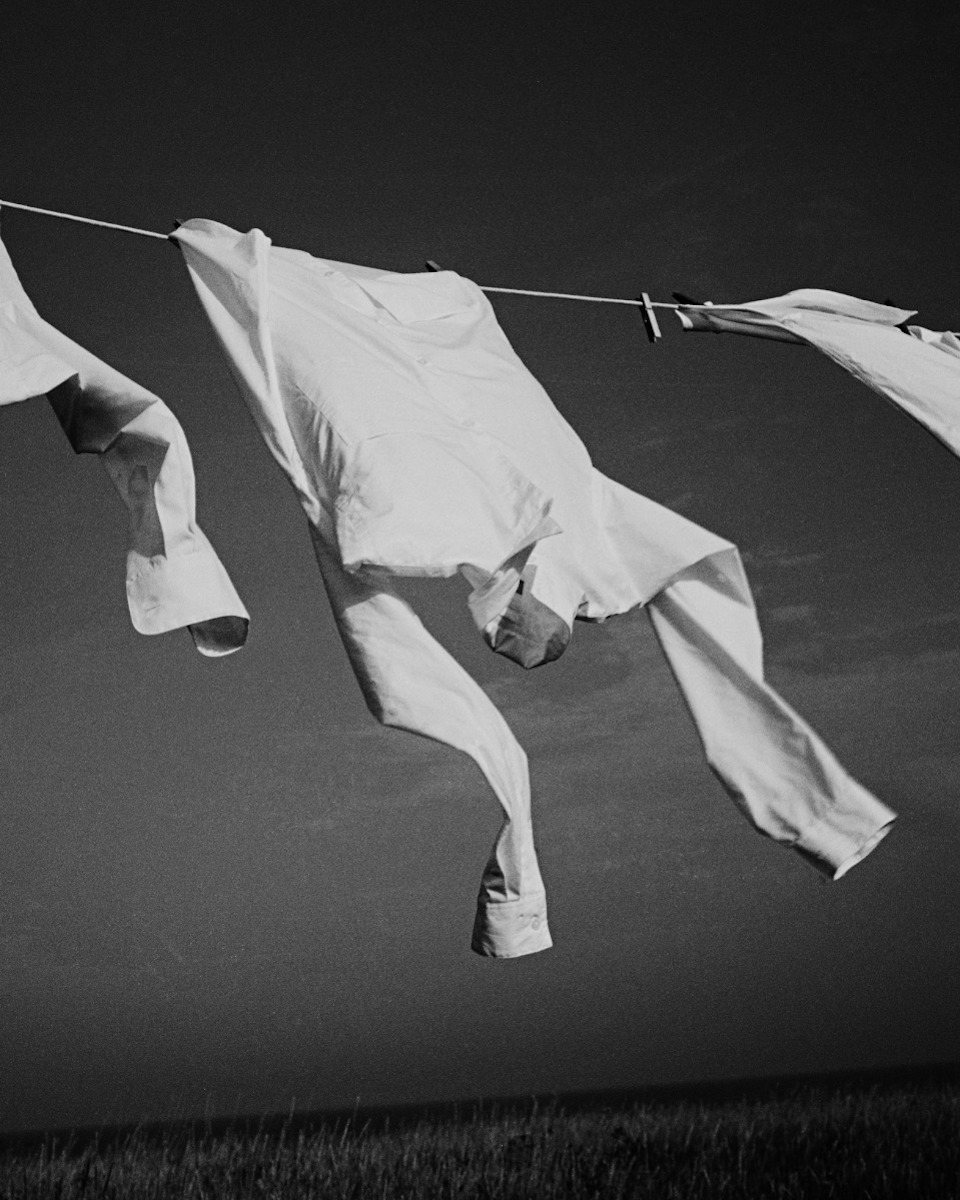

Sir John Vanbrugh: Seaton Delaval, Northumberland (1720-28)

© Thomas Deckker 2017

© Thomas Deckker 2017

One of the circular bastions in the garden wall.

At Seaton Delaval the circular bastions are vestigial to say the least - little more than garden walls, and indeed one has been absorbed into the adjacent farm wall. They were doubtless overlooked as they did not apper in the drawings in Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus Vol 3, published in 1725 when the house was under construction. They apper clearly in the historic Ordnance Survey maps, however. It is this small feature which illuminates the resemblance to Chambord and confirms the concept of a castle.

Seaton Delaval, Ordnance Survey

© Ordnance Survey 1920s

© Ordnance Survey 1920s

roll over for illustration of house and bastions

Thomas Deckker

London 2021

London 2021