thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

Eugène Hénard and the End of the 19th Century

2026

2026

Place de l'Opéra, Paris

photograph c. 1905

photograph c. 1905

Eugène Hénard and the End of the 19th Century

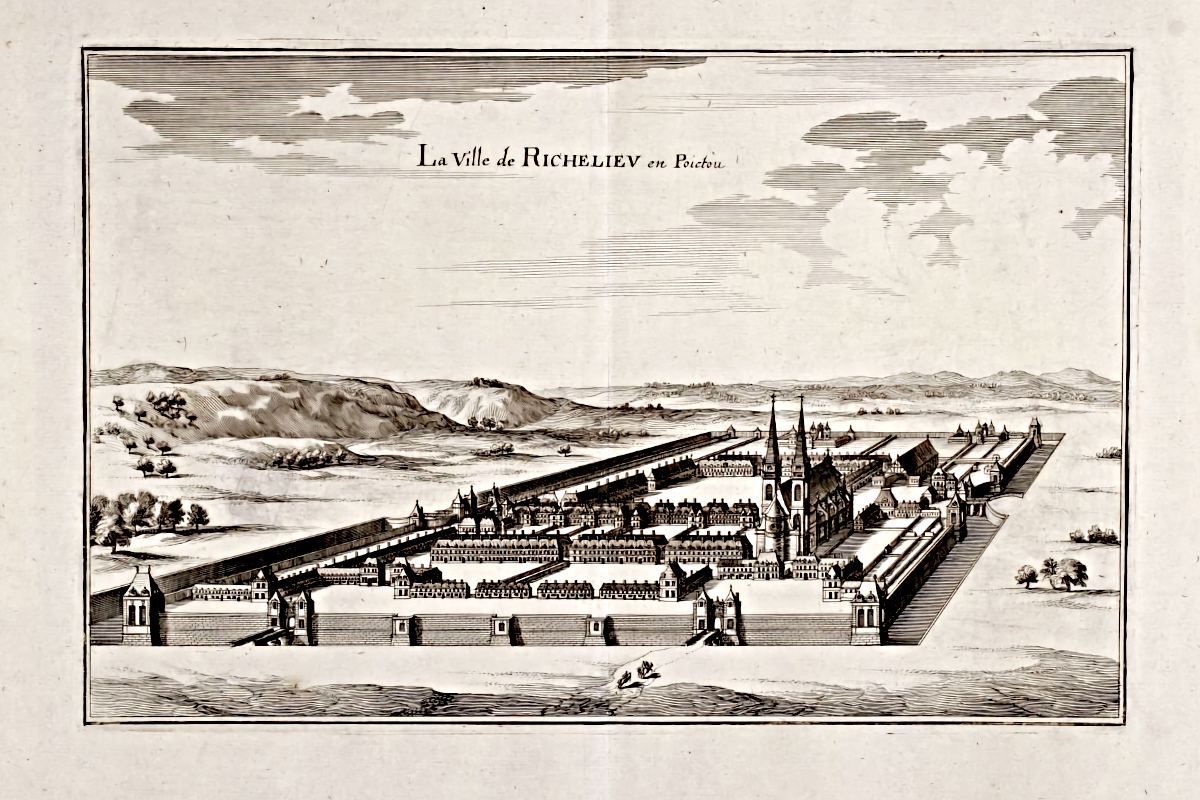

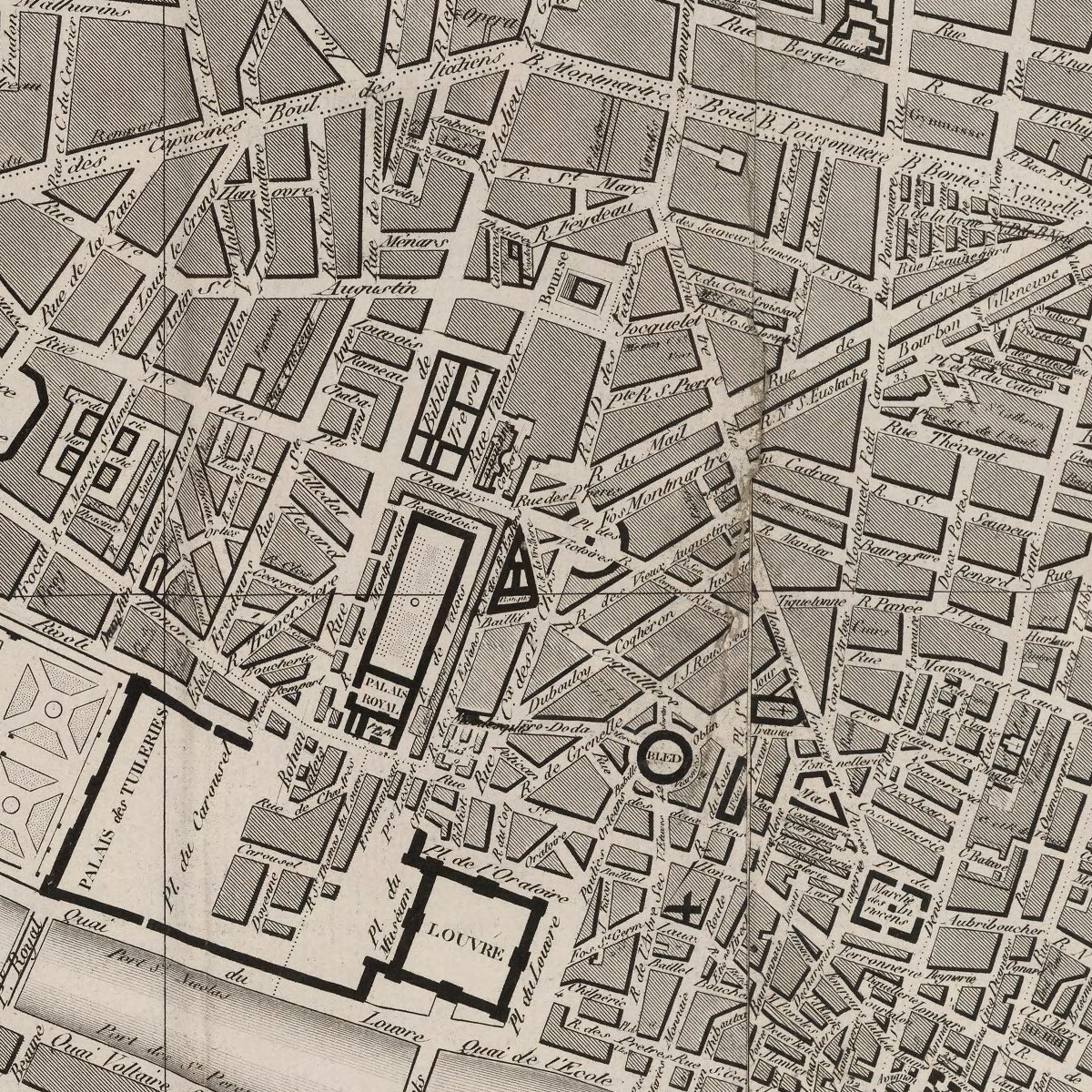

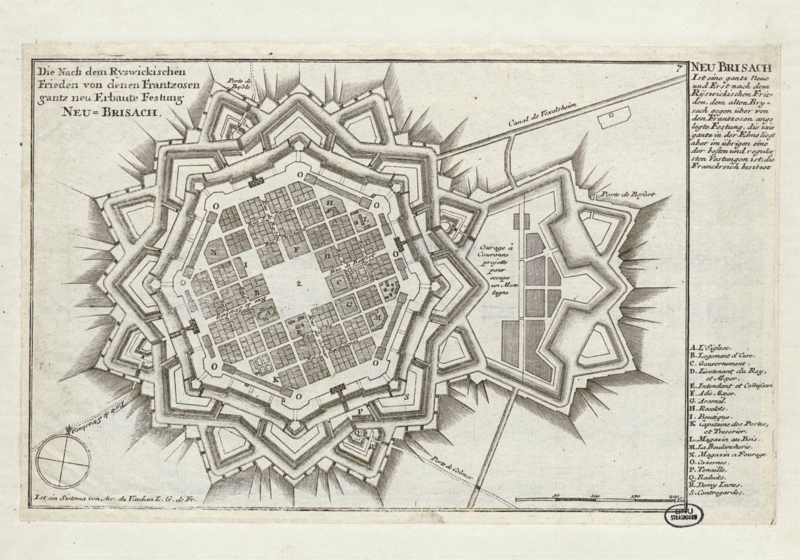

In 1910 the French architect and urban planner Eugène Hénard delivered a lecture at an RIBA conference on town planning. He was internationally famous for his Etudes sur les transformations de Paris, published between 1903 and 1909.[1] The conference was attended by architects and urban planners from all over the developed world, including the American architect and urban planner Daniel H. Burnham whose Plan for Chicago of 1909 was virtually a homage to Hénard.[2] It was publicly and enthusiastically supported by King George the Fifth. The proceedings were lavishly published after the conference. [3]

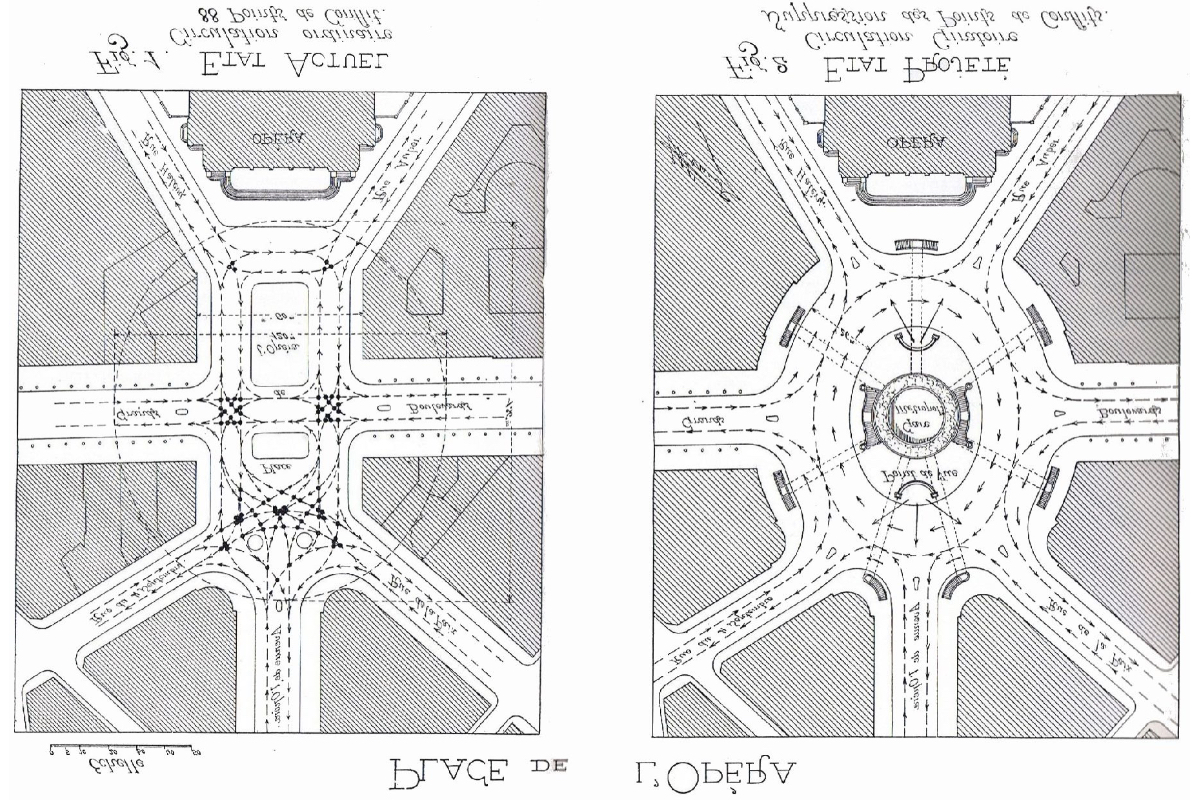

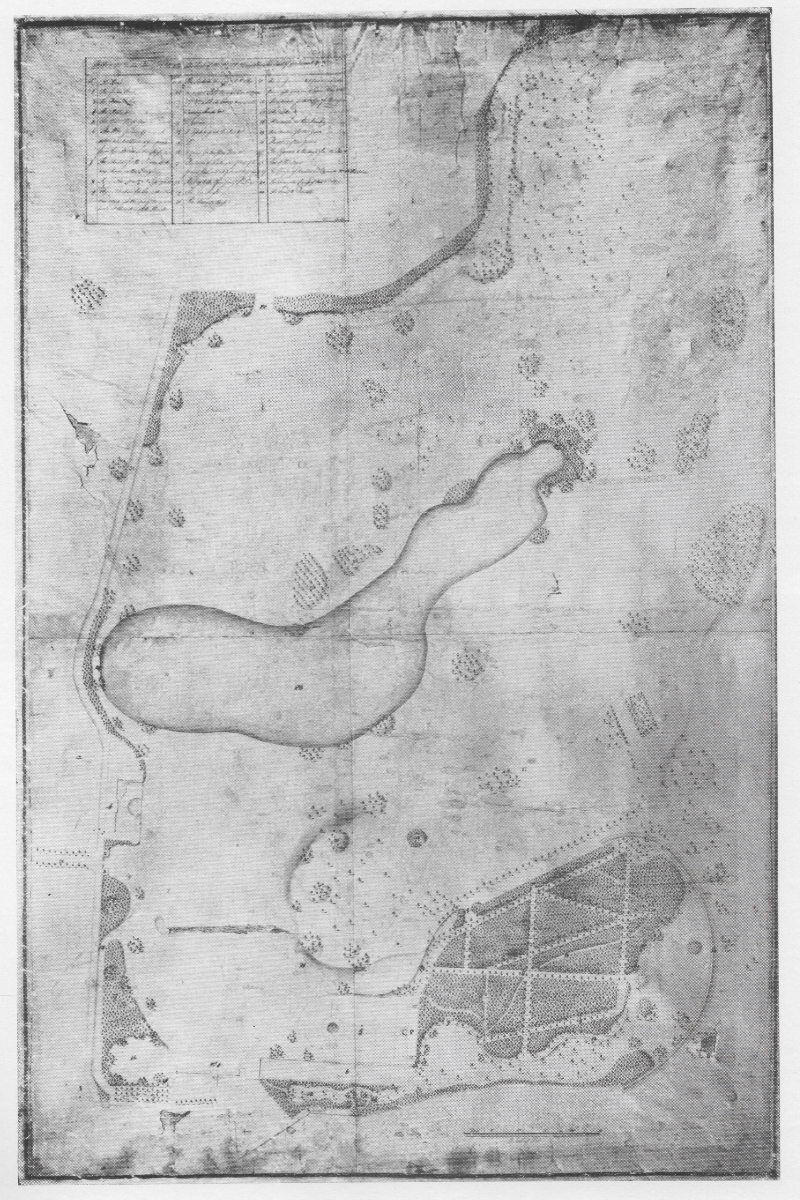

Eugène Hénard: proposal for Paris

from Transactions 1911

from Transactions 1911

the drawing is inverted and rotated to show it in the same orientation as the photograph above.

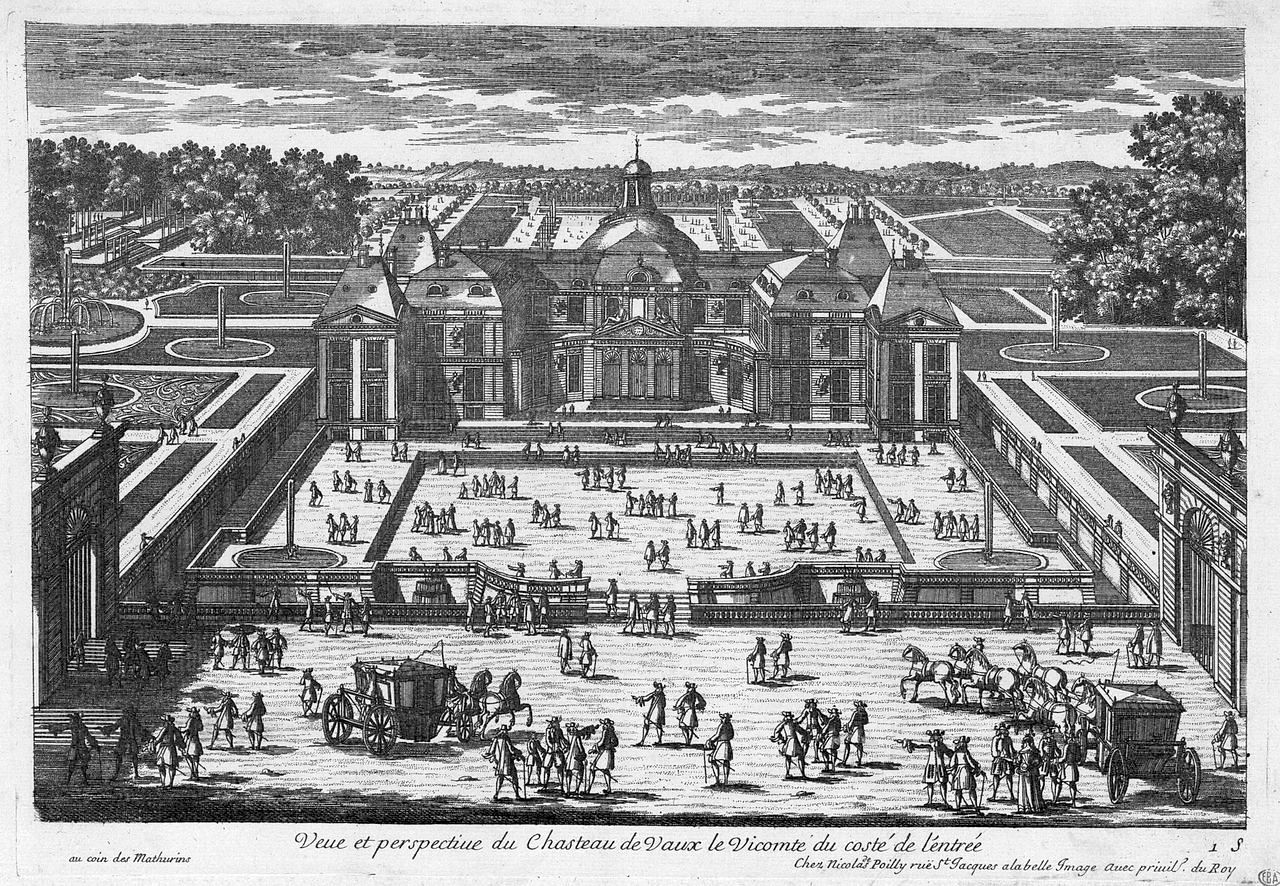

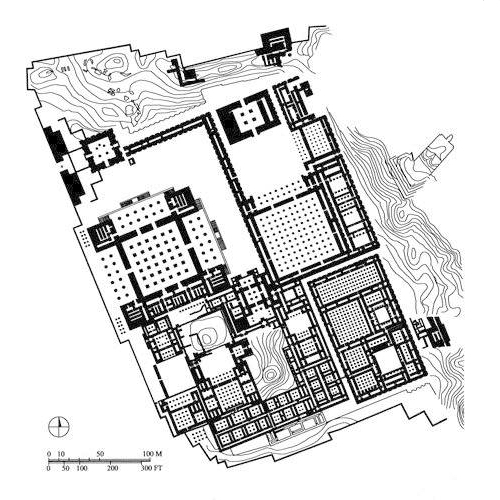

Hénard’s proposals for Paris consisted mainly of road widening schemes. One was for an enormous roundabout in front of the Opéra (volume 7), part of a wider scheme which included a road through the middle of the Palais-Royal (volume 5) to facilitate access to Les Halles market. The Opéra and the Palais-Royal were 2 celebrated buildings and public spaces: the Opéra, designed by Charles Garnier in 1861-75, was regarded as one of the most, if not actually the most, famous building of the late 19th century in Paris, and the Palais-Royal, designed by Jacques Lemercier in 1633-39, was a former royal palace and important public open space. [4] Several important buildings would have to have been demolished on all sides of the Place de l'Opéra for the roundabout, including the celebrated Cafe de la Paix and part of the newly-built Grand Hôtel (which appear on the left in the photograph above).

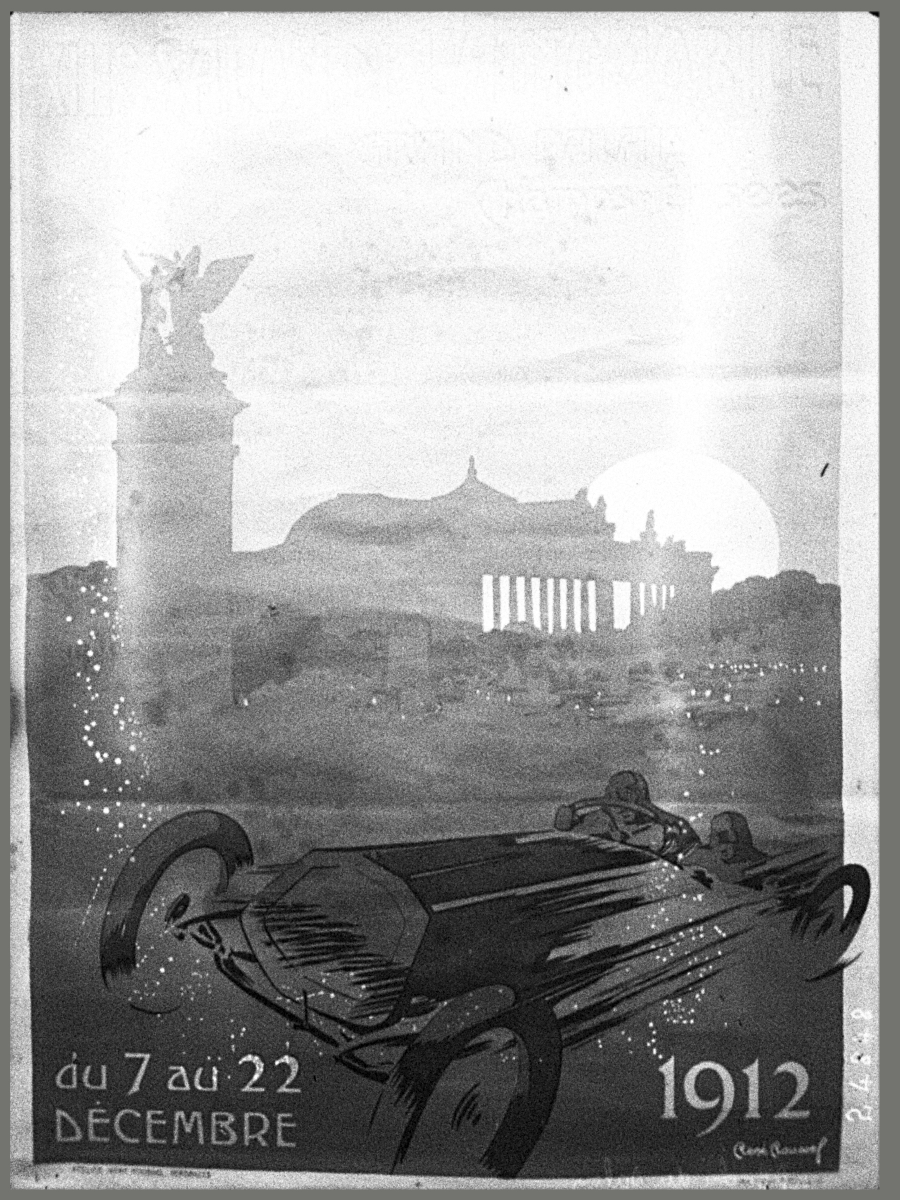

Affiche du XIIIe salon de l'automobile, Paris 1912 [Poster for the 13th Salon de l'Automobile, Paris 1912]

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

The poster shows the contrast between the excitement of speed and the Beaux-Arts architecture of the Grand Palais in which the salon was held.

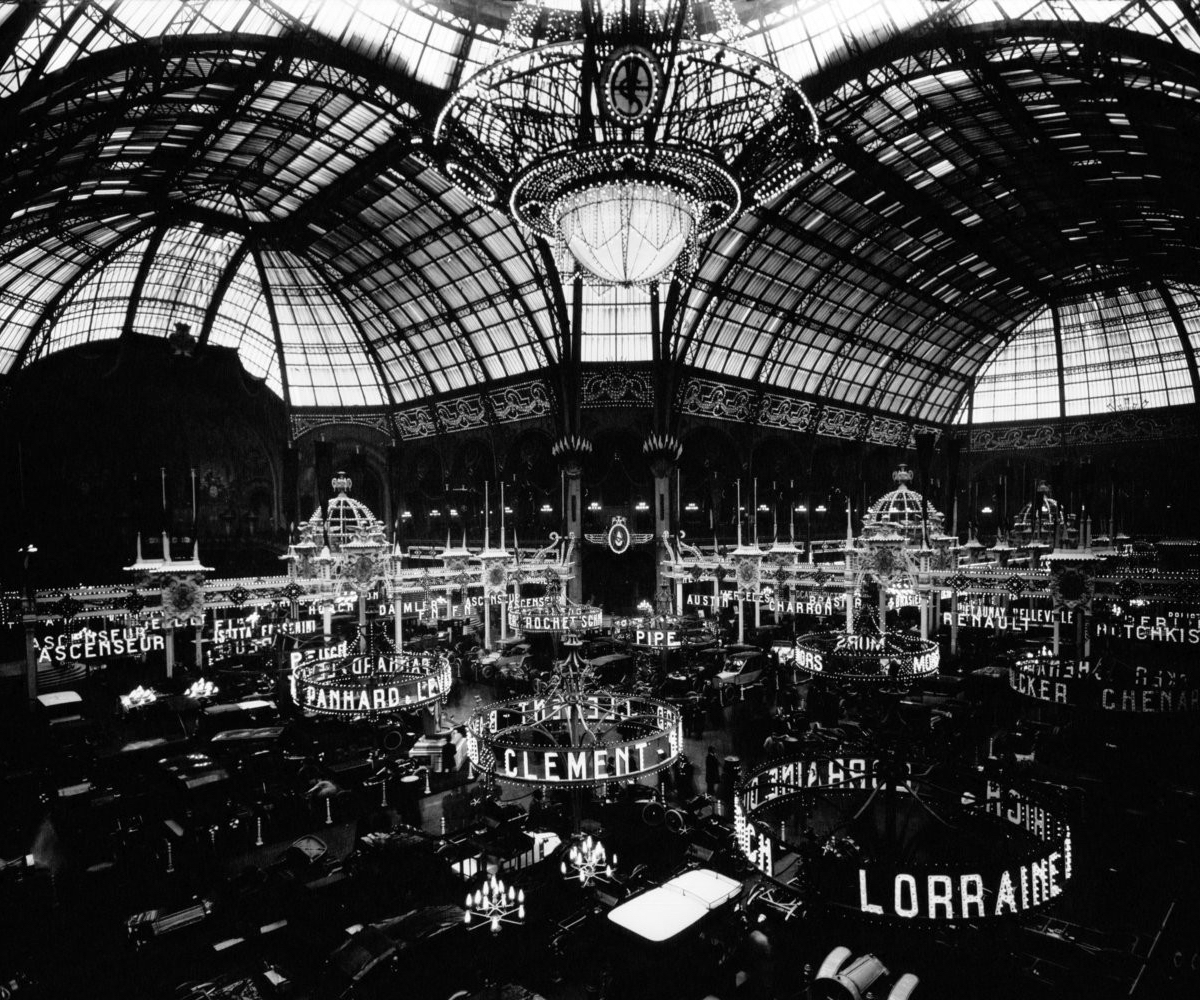

XIIIe salon de l'automobile, Paris 1912 [13th Salon de l'Automobile, Paris 1912]

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

The 13th Salon de l'Automobile was held in the Grand Palais, one of several Beaux-Arts iron-and-glass pavilions from the turn of the century in Paris. The Grand Palais was built for the Exposition Universelle [World’s Fair] of 1900, along with the Métro system. Manufacturers in France were the leading producers of luxury automobiles until the First World War, when they were overtaken by those in the United States, in particular Ford with the very popular and cheap Model T.

Recent and very comprehensive research papers have shown that increased personal mobility was a key social objective in Paris during the 20th century. There was at the time a true revolution in personal mobility, from cars and bicycles to women's clothes. The Métro opened in 1900 to provide transport for the Exposition Universelle [World’s Fair] of 1900. Automobiles were at the time restricted to the very wealthy and, judging from the photographs, traffic density was low. On the other hand, lorries, including the very advanced Berliet Type M launched in 1910, rapidly took over from horse-drawn vehicles, with their attendant problem of manure. It was thought at the time that there were no disadvantages - in particular air pollution - connected to motor vehicles. [5]

Hénard had studied, ironically, at the École des Beaux-Arts, the French School of Art and Architecture, rather than at is rival, the engineering-based École Polytechnique (which replaced the École des Ponts et Chaussées, or 'School of Bridges and Roads'). The École des Beaux-Arts was specifically oriented towards designing large public buildings, of which the Opéra was a flagship example. After graduating from the the École des Beaux-Arts, Hénard joined the Public Works Department of the City of Paris as an architect and began to gain recognition as a traffic engineer. [6]

Hénard presented his propsals for traffic management as scientific responses to mobility in the city, disregarding that they gave priority to one particular set of transport choices, particularly as the Métro was so successful. In London, the new buildings for Smithfield (Sir Horace Jones, 1866-67), the central wholesale meat market, were joined to the Underground and the basement contained large marshalling yards, thus mitigating a serious supply situation. Hénard's faith in technology had begun or had been nurtured during the 1889 Exposition Universelle [World’s Fair] in Paris, where he worked as an assistant on Victor Contamin's and Ferdinand Dutert's Palais des machines, at the time by far the largest vaulted iron structure in the world. One can see how architects, seduced by the engineering of structures, assumed technology could solve other, essentially political, problems. This leap in scope, from arranging circulation inside a building to managing circulation in cities, can be seen as a conceptual break in the role of the architect.

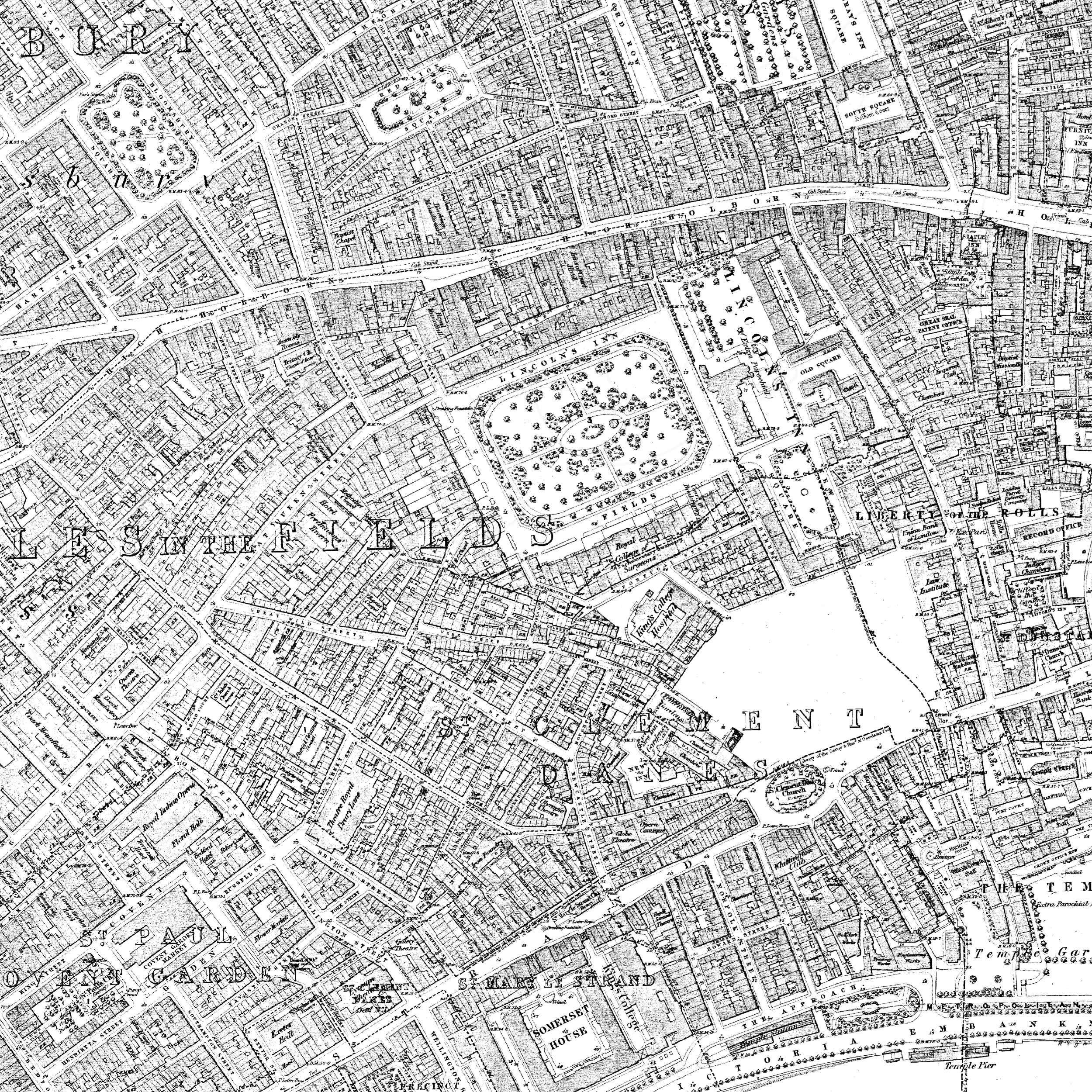

Aldwych in 1860

Roll over for Aldwych in 1910.

The boulevards in Paris are generally thought of as unique examples of cutting roads through urban fabric, but this is inaccurate. Firstly, many boulevards in Paris were actually along the lines of redundant fortifications, with a few linking boulevards to make a network. Secondly, Public Works Department in other cities were creating new roads at exactly the same time. In London, Regent Street (1811-25) had already been built, although as a royal development it does not belong with later, municipal, examples. Victoria Street, which cut through a slum in Pimlico, opened in 1851. Clerkenwell Road, 1874–78, and Rosebery Avenue, 1887-2, were cut through slums in Finsbury; Shaftesbury Avenue, 1886, through Soho. These Victorian streets are generally recognisable by the very poor architecture (Rosebery Avenue being an exception, as much of the work was undertaken under the LCC, which, in hindsight, marked a high point of architecture and urban design in London). After Henard's lecture, another road, Kingsway, opened in 1912, was cut through a notorious slum in Covent Garden and named in honour of King George the Fifth, who had so enthusiastically supported the RIBA conference. Burnham's Plan for Chicago was implemented partially and piecemeal, mainly as road widening, and he went on to be a consultant on the Macmillan Plan for Washinton D.C. generally considered a masterpiece of Beaux-Arts urban design. Both of these plans employed large diagonal boulevards as strategic design devices.

François Mazois and Antoine Tavernier: Passage Choiseul, Paris (1827)

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

Paris is regarded by some political theorists as the 'Capital of the Nineteenth Century' or the 'Capital of Modernity'. Various academic theories (some far-fetched) have been put forward to explain the creation of Hausmann's boulevards, but their main purpose was to create a public realm to balance what was still a collection of intensely private spaces and social practices. The creation of the boulevards was the first time in urban planning in which urban spaces had been made deliberately for people to walk, even without any purpose, and cafes, shops, the first department stores and even opera houses supported and were reciprocally supported by, them. Circulation of other kinds - horses, goods, sewage etc. - was a complement. By contrast the roads proposed by Henard were through roads deliberately without connection to their surroundings. Streets have always supported the dual objectives of access to the buildings on either side and through traffic, but motorised traffic changed the nature of this balance dramatically. [7]

Avenue de l'Opéra, Paris

photograph c. 1905

photograph c. 1905

Henard’s proposal for the Place de l'Opéra signified a major break with the concept of 19th century urban space. Rather than being an isolated building, the Opéra, the Place de l'Opéra and the Avenue de l’Opéra were conceived as a unity. The evidence of contemporary photographs shows that in the early 20th century, when Hénard published his Etudes, these were still mainly pedestrian streets and pedestrians could enter the Opéra through the arcade. The grand entrance front was unashamedly a symbolic gesture, but it also had a very practical use as it was the main pedestrian entrance to the building. One can read a continuity of space from the Place and Avenue into the vestibule. The groundwork, therefore, for what is generally considered to be the 'Modernist' destruction of Paris actually had its foundations laid by an architect deeply embedded within the architectural establishment in the early 20th century.

Charles Garnier: l'Opéra, Paris (1861-75)

photo Thomas Deckker 1996

photo Thomas Deckker 1996

It is ambiguous whether the entrance hall is an internal or external space. This is a peculiarity of buildings designed by architects from the École des Beaux-Arts, doubtless a result of the enormous areas devoted to internal circulation. Here it reinforces the connection to the street.

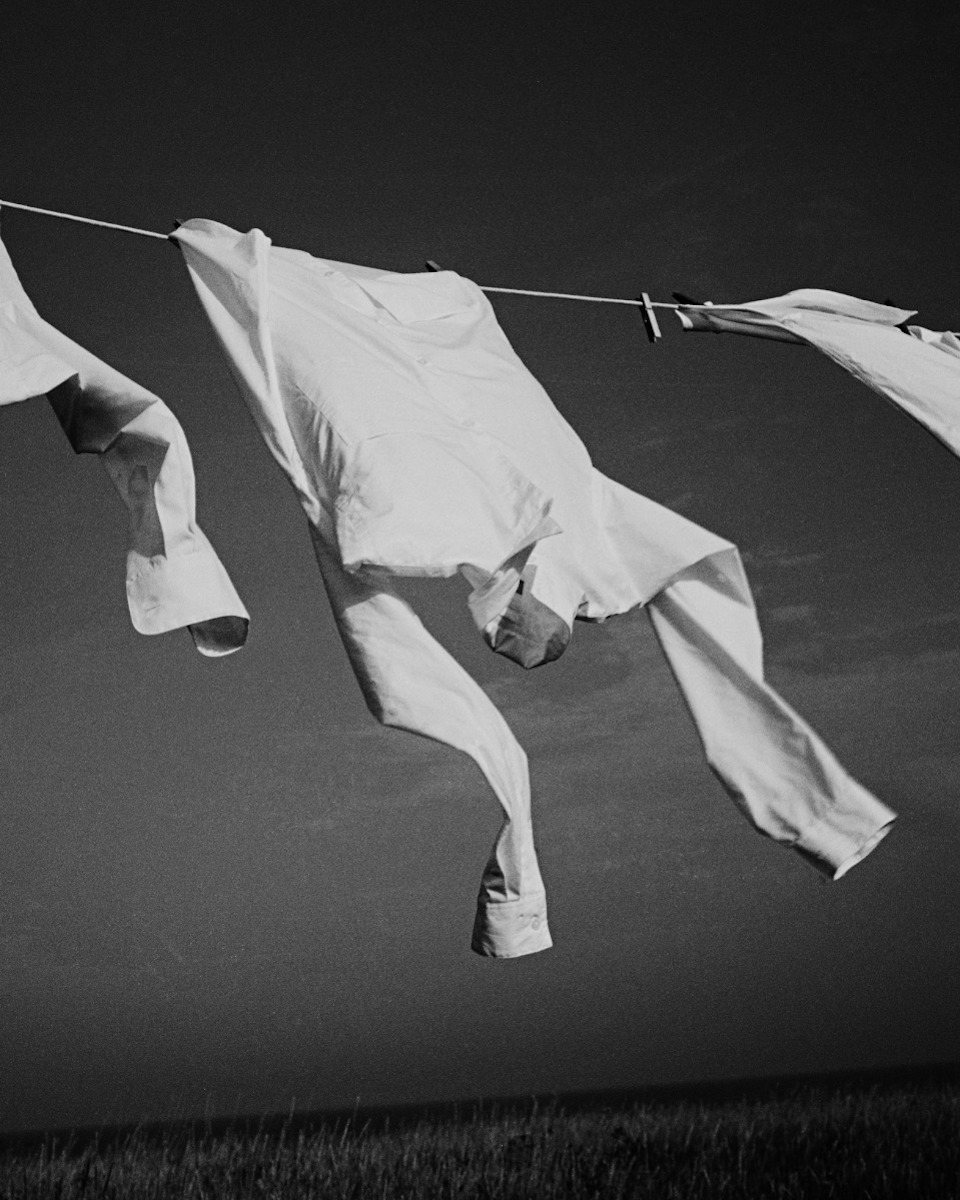

What did they wear?

Charles Frederick Worth: Evening Dress,1889 [C.I.59.20]

The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A dress by Charles Frederick Worth, who initiated the system of haute couture in Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century. Worth was actually English and moved to Paris to develop his - eventually highly successful - business.

This dress is made of embroidered silk, in Worth's characteristic asymmetrical style which allowed for a long train. One can imagine the owner wearing this dress ascending the stair of the Opéra, its dramatic power matching that of the building, to attend a performance of Guiseppe Verdi's La Traviata, the life and death of a courtesan in Paris in the mid-19th century.

This dress is made of embroidered silk, in Worth's characteristic asymmetrical style which allowed for a long train. One can imagine the owner wearing this dress ascending the stair of the Opéra, its dramatic power matching that of the building, to attend a performance of Guiseppe Verdi's La Traviata, the life and death of a courtesan in Paris in the mid-19th century.

Charles Garnier: l'Opéra, Paris (1861-75)

photo Thomas Deckker 1996

photo Thomas Deckker 1996

One half of the grand staircase.

We can see with the benefit of hindsight that this style of dressing and the social conventions that went with it had largely disappeared by the first decade of the 20th century, although doubtless on the ground it appeared to continue. The Rational Dress Society was founded in 1881, with goals including lessening restrictions on personal mobility for women (intended to facilitate the use of the newly-invented bicycle) and promoting comfort.

Paul Poiret: Evening Dress "Théâtre des Champs-Élysées", 1913 [2005.193a-g]

The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This dress was worn by Paul Poiret's wife and muse Denise Poiret to the premiere of Igor Stravinsky's Sacre du Printemps [The Rite of Spring], (one of his 3 great ballets for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and regarded as the first 'modern' music) for the opening of the Auguste Perret's Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on April 1, 1913. Contrary to popular histories, there is no evidence that this performance caused a riot. The Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev, dancer Vaslav Nijinsky and composer Igor Stravinsky had financially viable and critically successful careers in Paris because it was receptive to the avant-garde. According to the Costume Institute, Denise Poiret's "svelte, gamine beauty... represented both the ideal of classical beauty and the paradigm of the modern woman."

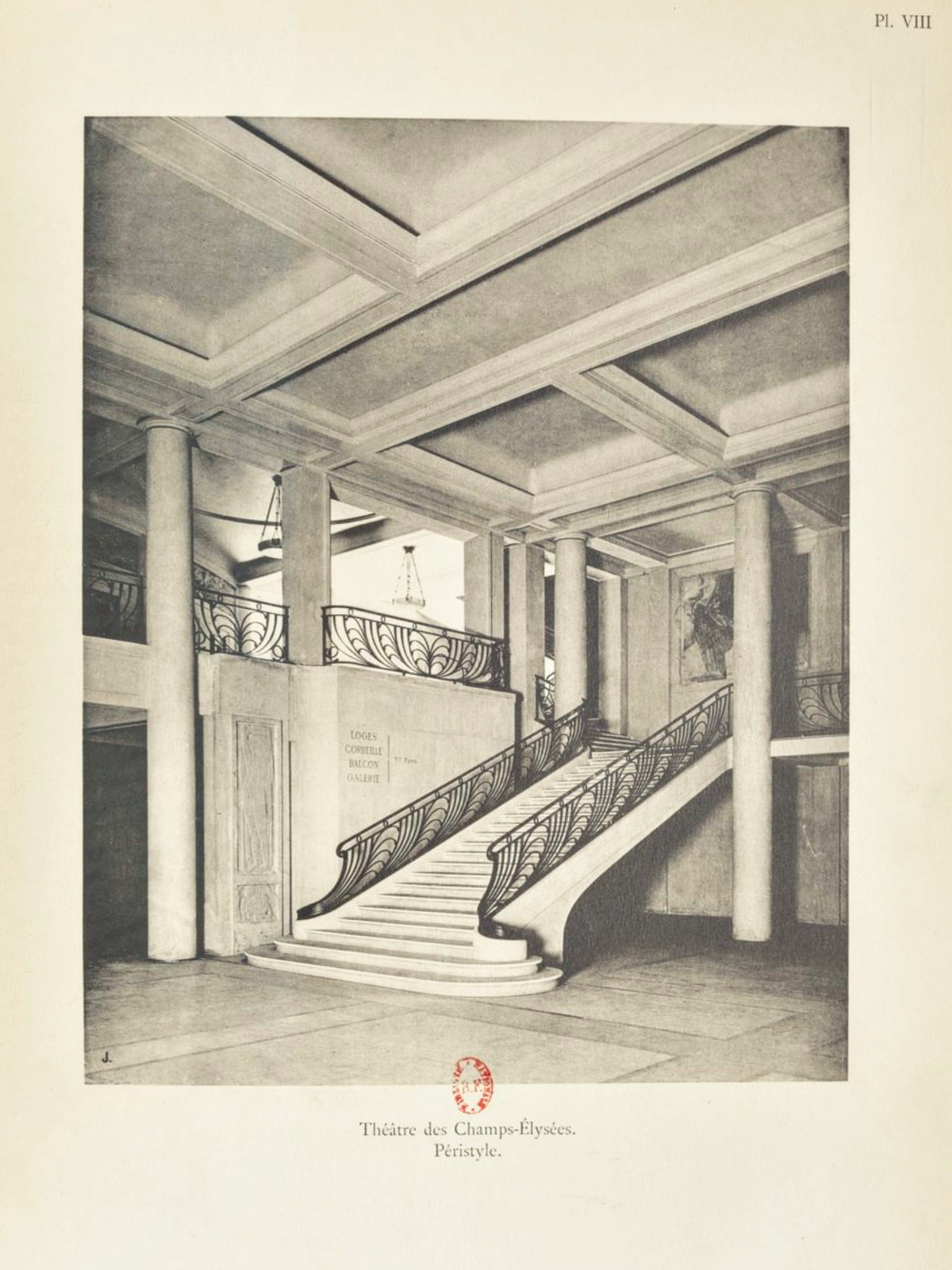

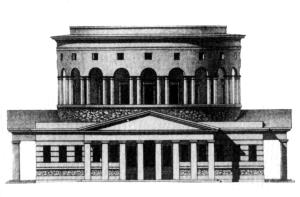

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées was the first theatre with a reinforced concrete frame, although it is not expressed as such along the street elevation. It is not clear what difference this makes to the building as a space for performance or spectacle, but the difference in appearance is striking: it is almost devoid of decoration. [8]

Auguste Perret: Théâtre des Champs-Élysées 1913 Plate VIII from Paul Jamot: A. G. Perret et l'architecture du béton armé (Paris and Brussels: Librairie Nationale 1927)

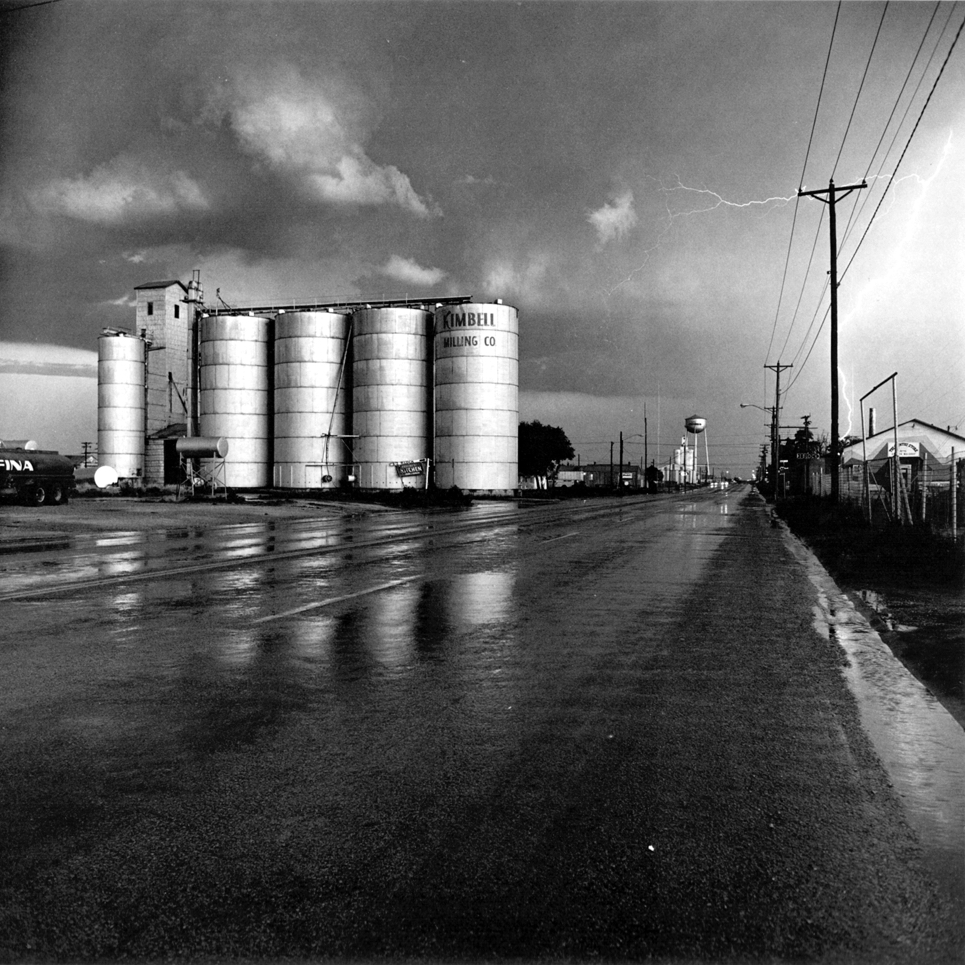

"The Life and Death of Urban Highways"

The uncritical acceptance of technology as a supposedly scientific solution to the problem of transport in cities went unchallenged throughout the developed world after WWII. It became politically expedient to develop urban highways in the United States to support mass suburbanisation, a result, in fact the purpose, of the Servicemen's Readjustment Act (1944, popularly known as the G.I. Bill). It was a short step from cutting roads through urban fabric to building elevated highways. These received substantial government suport under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and were widely copied throughout the world. In London, trains to Smithfield market were ended, and elevated motorways built (under the GLC, which in hindsight marked a low point in urban design in London). It was thought at the time that there were no disadvantages connected to them. They became controversial when it became apparent that they caused immense blight to the areas they crossed, in particular areas of racially and socially disadvantaged citizens. Ironically, urban highways such as Robert Moses's Parkways in New York City of the 1920s and 1930s were regarded as the pinnacle of integrated urban highway design. [9]

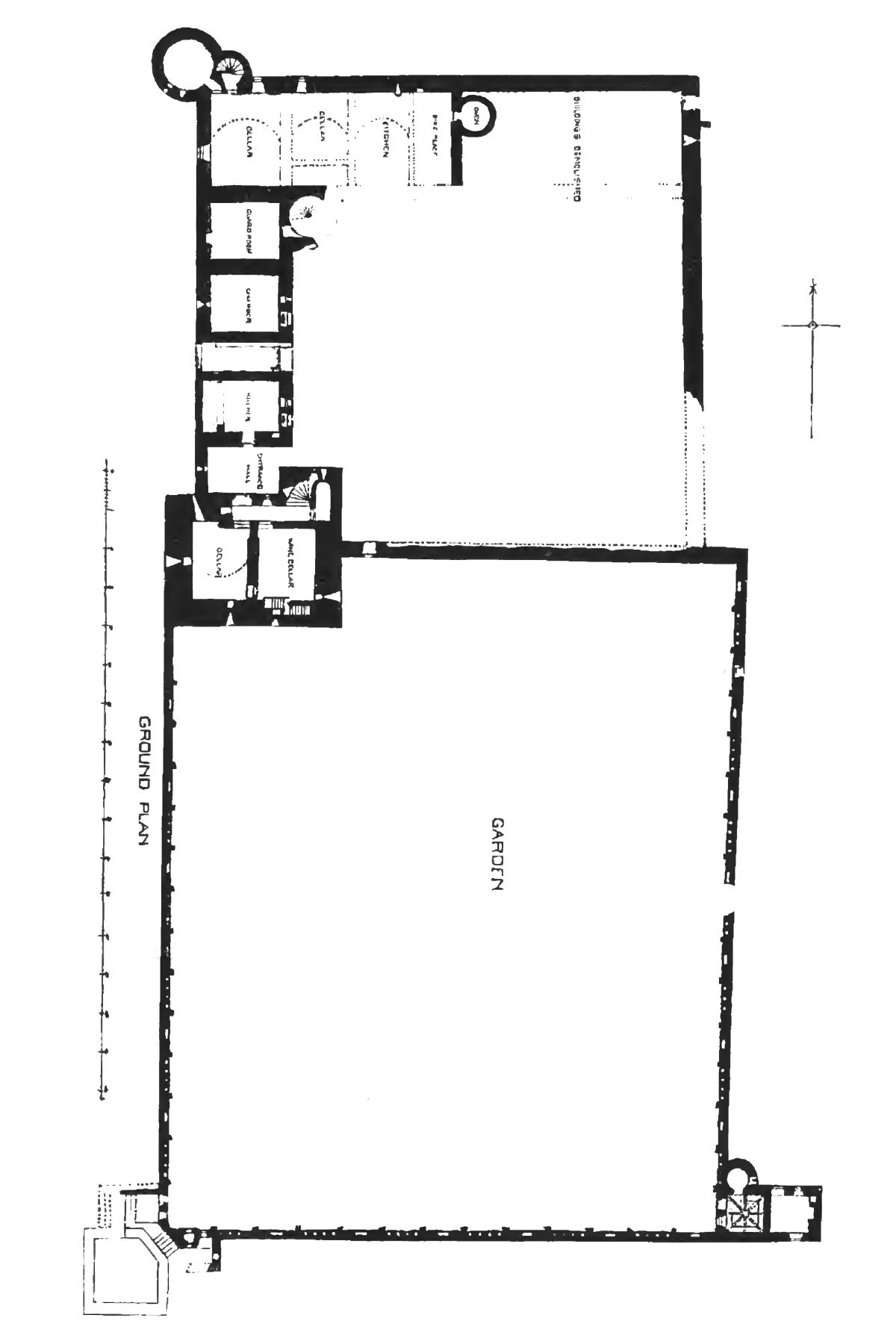

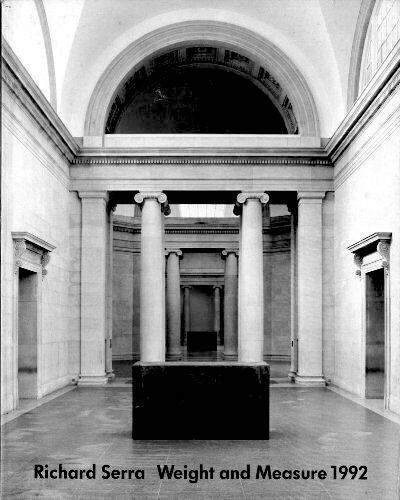

Sir William Chambers: Somerset House, London (1775-78)

photo Thomas Deckker 2012

photo Thomas Deckker 2012

This popular public space, previously a car park for the adjacent HMRC offices, is used for all kinds of events, including skating in the winter, temporary exhibitions and music shows. It is also the entrance to the Courtauld Gallery.

The reaction to urban highways began in the United States in the 1960s, when the activist Jane Jacobs (among others) successfully challenged Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have destroyed Greenwich Village, at the time the bohemian quarter. Elevated urban highways began to be demolished, removing at a stroke the urban blight they had caused. Public antagonism to road widening in Paris began in earnest after the demolition of Les Halles market in 1971. There are now organisations dedicated to developing sustainable transport, and quality of life has become an important factor in urban design. In London, several important public spaces have been rehabilitated from parking lots, such as the courtyard of Somerset House (Sir William Chambers, 1775-78). It marks in a modest way the recovery of public space lost in Henard's proposal for a roundabout in front of the Opéra. [10]

Footnotes

1. Eugène Hénard: 1: Projet de prolongement de la rue de Rennes avec pont en X sur la Seine - 1903. 2: Les Alignements brisés. La question des fortifications et le boulevard de la Grande ceinture - 1903. 3: Les Grands espaces libres. Les parcs et jardins de Paris et de Londres - 1903. 4: Le Champ de Mars et la galerie des machines. Le parc des sports et les grands dirigeables - 1904. 5: La Percée du Palais-Royal. La nouvelle grande Croisée de Paris. - 1904. 6: La Circulation dans les villes modernes. L'automobilisme et les voies rayonnantes de Paris - 1905. 7 : Les Voitures et les passants. Carrefours libres et carrefours à giration - 1906. 8: Les Places publiques. La Place de l'Opéra. Les trois colonnes - 1909. (Paris: Champion). ↩

2. Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett: Plan for Chicago (Chicago, Commercial Club 1909). ↩

3. Town Planning Conference, London, 10-15 October 1910: Transactions (London: Royal Institute Of British Architects 1911). ↩

5. See, for example, Arnaud Passalacqua: 'From the History of Transport in Paris to the History of Mobility in Greater Paris?' in Mobility in History, vol. 7 no. 1(2016) pp. Pages: 133–139 and Mathieu Flonneau: 'City infrastructures and city dwellers: Accommodating the automobile in twentieth-century Paris' in The Journal of Transport History vol.27, no. 1 (2006) pp. 93–114. ↩

6. Jean Paul Carlhian: ‘The École des Beaux-Arts: Modes and Manners’ in the Journal of Architectural Education vol. 33 no. 2 (1979) p.17. ↩

7. Walter Benjamin: The Arcades Project [Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press 2002; translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin]. David Harvey: Paris, Capital of Modernity (New York and London: Routledge 2003). ↩

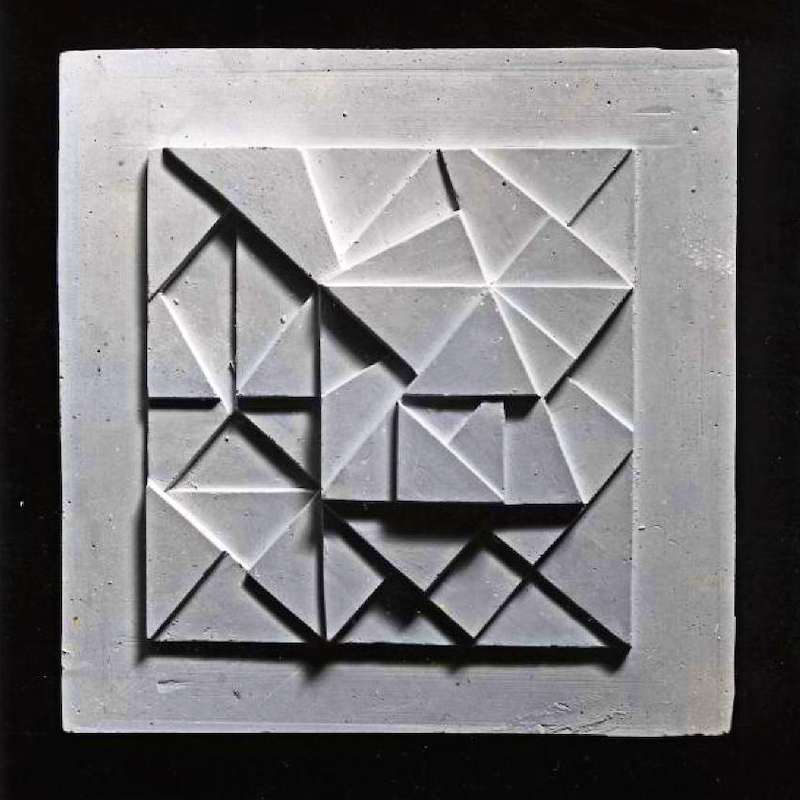

8. Peter Reyner Banham: Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (London: The Architectural Press and New York: Praeger 1960). ↩

9. Timothy Davis: The American Motor parkway in Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscape vol 25 number 4 Oct-Dec 2005 pp.219-241. ↩

10. See The Life and Death of Urban Highways, a report funded by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) and EMBARQ. Downloadable from ITDP. Jane Jacobs: The Death and Life of Great American Cities: The Failure of Town Planning (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1965; 1st publ. 1961). ↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2026

London 2026

![Charles Frederick Worth: Evening Dress,1889 [C.I.59.20] The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York](comm_images/C.I.59.20.jpg)

![Paul Poiret: Evening Dress 'Théâtre des Champs-Élysées', 1913 [2005.193a-g] The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York](comm_images/2005.193a-g.jpg)